Communism ...

or Capitalism?

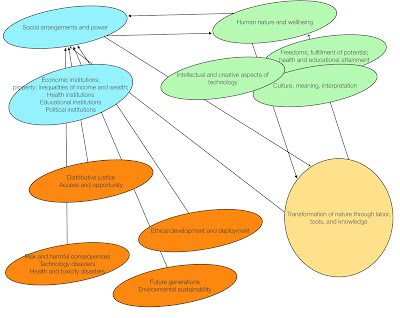

A joke from Poland in the 1970s: "In capitalism it is a question of man's exploitation by man. In communism it is the reverse."A modern social system is an environment where millions of people find opportunities, develop their talents, express their beliefs, and earn their livings within the context of a set of economic and political institutions. Specific institutions of property, power, ideology, education, and healthcare create an environment within which citizens of all circumstances pursue their life interests. Individuals exercise their freedoms through the institutions within which they live, and those institutions also determine the quality and depth of social resources available to the individual that determine the degree to which he or she is able to develop talents and skills and gain access to opportunities. Institutions create constraints on freedom of choice that range from the nearly invisible to the intensely coercive. Institutions create inequalities of opportunity and outcome for different groups of citizens; rural people may have more limited access to higher education, immigrant and minority communities may experience discrimination in health and employment; and so on. Further, social systems differ in the balance they achieve between "soft" constraints (market, education, regional differences) and "hard" constraints (police, regulations governing behavior, extra-legal uses of violence).

To describe a set of institutions and a population of individual actors as a system has a number of implications, some of which are unjustified. The idea of "system" suggests a kind of functional interconnection across its components, with needs in one subsystem eliciting adjustments in the activities of other subsystems to satisfy those needs. This mental model is misleading, however. Better is the ontology of "assemblage" discussed frequently here (link, link, link). This is the idea that a complex social thing is the unintended and largely undesigned accumulation of multiple independent components. One set of processes leads to the development of the logistics infrastructure of a society; another set of processes leads to the development of the institutions of government; and yet other path-dependent and contingent processes contribute to the system of labor education, management, and discipline that exists in a society. These various institutional ensembles are overlaid with each other; sometimes there are painful inconsistencies among them that are resolved by entrepreneurs or officials; and the result is a heterogeneous and largely unplanned agglomeration of social arrangements and practices that add up to "the social system".

A central premise of some classics of social theory, including Marx, is that the institutions through which social interactions take place form large and relatively stable configurations that fall into fairly distinct groups -- feudalism, capitalism, communism, socialism, social democracy, authoritarianism. And different configurations of institutions do better or worse in terms of the degree to which they allow their members to satisfy their needs and live satisfying lives. The ontology associated with the theory of assemblage, however, is anti-essentialist in a very important sense: it denies that there are "essentially similar configurations" of institutions that play crucial roles in history, or that there is a tendency towards convergence around "typical" ensembles of institutions. In particular, it suggests that we reject the idea that there are only a few historically possible configurations of institutions -- capitalism, socialism, authoritarianism, democracy -- and rather analyze each social order as a fairly unique configuration -- assemblage -- of specific institutional arrangements.

This perspective casts doubt on the value of singling out "capitalism," "liberal democracy," "religious autocracy," "apartheid society," "military dictatorship," or "one-party dictatorship" as schemes for understanding distinctive and sociologically important patterns of un-freedom. Rather than considering these different "ideal types" of social-political systems as structures with distinctive dynamics, perhaps it would be more satisfactory to consider the problem from the point of view of the citizens of various societies and the degree to which existing social, political, and economic institutions serve their development as full and free human beings.

Amartya Sen's framework for understanding human wellbeing in Development as Freedom is valuable in this context (link). Sen understands wellbeing in terms of the individual's ability to realize his or her capabilities fully and to live within an environment enabling as much freedom of action as freely as possible. Sen's framework gives a powerful basis for paying close attention to inequalities within society; a society in which one-third of the population have exceptional freedom and opportunities for development, one-third have indifferent attainments in these crucial dimensions, and one-third have extremely limited freedoms and opportunities is plainly a less just and desirable society than one in which everyone has the same freedoms and a relatively high level of opportunities for development -- even if the average attainment for the population is the same in the two scenarios.

This prism permits us to attempt to understand the structural characteristics of society -- political, cultural, religious, economic, or civic -- in terms of the effects that those institutional arrangements have on the freedoms and capacity for development of the population. This is the underlying rationale for the Human Development Index, but the HDI is primarily focused on development rather than freedom.

We might try to evaluate the workings of a given ensemble of social and political institutions by devising an index of human wellbeing and freedom that can be applied to each society. Examples of indexes along these lines include the Human Development Index, the Opportunity Index, and the Cato Institute Freedom Index. Every index is selective. It is interesting and important to observe, for example, that political freedom plays no role in the Human Development Index, while the Cato Institute index pays no attention to the prerequisites of freedom: access to education, access to health care, freedom from racial or ethnic discrimination.

So each of these indices is limited as a scheme for evaluating the overall success a particular institutional configuration has in creating a free and enabling environment for its citizens. But suppose we had a composite index that reflected both freedom (broadly construed) and wellbeing? Such an index might look something like this:

- Rule of law

- Security and safety

- Movement

- Religion

- Association, assembly, and civil society

- Expression and information

- Identity and relationships

- access to quality education

- access to quality healthcare

- freedom from racial, ethnic, and gender discrimination in employment, education, housing, and other social goods

- equality of opportunity

Using an index like this, we could then ask important comparative questions: How do ordinary citizens fare under the institutions of contemporary Finland, Spain, China, Russia, Nigeria, Brazil, Romania, France, and the United States? An assessment along these lines would put us in a position to give a normative evaluation of the various social systems mentioned above: what social, political, and economic arrangements do the best job of securing each of these freedoms and opportunities for all citizens? Under what kinds of institutions -- economic, political, social, and cultural -- are citizens most free and most enabled to fully develop their capacities as human beings?

It seems evident that the answer to this question is not very esoteric or difficult. Freedom requires the rule of law, respect for equal rights, and democratic institutions. Real freedom requires access to the social resources that permit an individual to fully develop his or her talents. A decent life requires a secure and adequate material standard of living. These obvious truths point towards a social system that embodies the protections of a constitutional liberal democracy; extensive public support for the social resources necessary for full human development (education, healthcare, nutrition, housing); and an extensive social welfare net that ensures that all members of society can thrive. There is a name for this set of institutions; it is called social democracy. (Here are several earlier posts that reach a similar conclusion from different starting points; link, link.)

And where are the social democracies in the world today? They are largely the Nordic countries: Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland. Significantly, these five countries consistently rank in the top ten countries in the World Happiness Report (link), a rigorous and well-funded attempt to measure citizen satisfaction with the same care as we measure GDP or national health statistics. The editors of the 2020 report describe the particular success of Nordic societies in supporting citizen satisfaction in these terms:

From 2013 until today, every time the World Happiness Report (WHR) has published its annual ranking of countries, the five Nordic countries – Finland, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Iceland – have all been in the top ten, with Nordic countries occupying the top three spots in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Clearly, when it comes to the level of average life evaluations, the Nordic states are doing something right, but Nordic exceptionalism isn’t confined to citizen’s happiness. No matter whether we look at the state of democracy and political rights, lack of corruption, trust between citizens, felt safety, social cohesion, gender equality, equal distribution of incomes, Human Development Index, or many other global comparisons, one tends to find the Nordic countries in the global top spots.And here is their considered judgment about the circumstances that have led to this high level of satisfaction in the Nordic countries:

We find that the most prominent explanations include factors related to the quality of institutions, such as reliable and extensive welfare benefits, low corruption, and well-functioning democracy and state institutions. Furthermore, Nordic citizens experience a high sense of autonomy and freedom, as well as high levels of social trust towards each other, which play an important role in determining life satisfaction. (131)The key factors mentioned here are worth calling out for the light they shed on the current dysfunctions of politics in the United States: effective institutions, extensive welfare benefits, low corruption, well-functioning democracy, a limited range of economic inequalities, a strong sense of autonomy and freedom, and high levels of social trust and social cohesion. It is evident that American society is being tested in each of these areas by the current administration, and none more so than the areas of trust and social cohesion. The current administration actively strives to undermine both trust and social cohesion, and goes out of its way to undermine confidence in government. These are very disturbing signs about what the future may bring. Severe inequalities of income, wealth, and social resources (including especially healthcare) have become painfully evident through the effects of the Covid-19 epidemic. And the weakness of the social safety net in the United States has left millions of adults and children in dire circumstances of unemployment and hunger. The United States today is not a happy place for many of its citizens.