There is certainly a working class in the United States, and it is a majority of the population (persons who earn their livelihood through wage-paying employment). But it is highly fragmented, mostly in the service sector, unorganized, and often disinclined to believe in the possibility of serious social change. A recent Brookings research report by Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman on low-wage workers provides a clear analysis of the current situation (link). Their report is based on US Census data (American Community Survey 2012-2016). Low-wage workers make up 44% of the US workforce (53 million workers). Median annual earnings of low-wage workers was $17,950 in 2016.

Once Ross and Bateman have defined the criteria for "low-wage workers", they are able to perform a great deal of useful analysis on the resulting population. Where do low-wage workers find jobs? These are the jobs that represent about half of low-wage workers: retail sales workers, information and records clerks, cooks and food preparation workers, building cleaning workers, material moving workers, food and beverage serving workers, construction trades workers, material recording, scheduling, dispatching, and distributing workers, motor vehicle operators, and personal care and service workers (such as child care workers and patient care assistants (Table 3, 11). The authors partition the data into nine clusters, distinguished by age and educational attainment. The largest cluster (cluster 4) is the age group 25-50, high school or less, with 27.8% of the low-wage population. This is also the largest age group overall, with 56.5% of the low-wage population.)

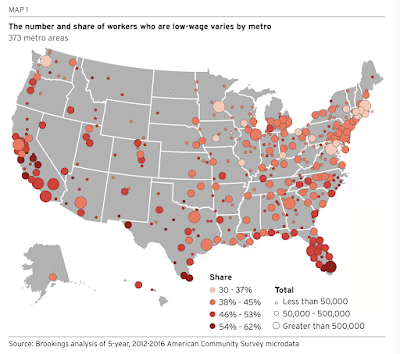

This map provides information about the absolute number of low-wage workers in US metropolitan areas and the share of low-wage workers in each metro area. The larger the circle the greater the absolute number, and the deeper the shade of orange, the higher the share of how-wage workers in that metro. Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach Metro has the highest absolute number of low-wage workers (1.206 million, representing 55% of the wage workforce).

How much economic mobility exists for low-wage workers? Very little, the authors report; only 5% of low-wage workers found a better-paying job within a 12-month period:

Research on whether low-wage jobs are springboards or sinkholes is not encouraging. The economic mobility of low-wage workers is limited—many remain in low-wage jobs over time, even as they rely on their earnings to support themselves or their families. Women, people of color, and those with low levels of education are the most likely to stay in low-wage jobs. One study found that, within a 12-month period, 70% of low-wage workers stayed in the same job, 6% switched to a different low-wage job, and just 5% found a better job. (39)

The authors offer a handful of policy recommendations to address the human hardships associated with low-wage jobs. First concerns education and skill-development. "There is a considerable body of evidence and practical knowledge on establishing and operating workforce programs that prepare workers—primarily those without college degrees—for in-demand jobs. That is not to say it is easy, however, or adequately funded, or that the knowledge is always implemented" (40). Programs for skill development can be funded by by public and private organizations, including Federal and local government and supported by industry and non-profit foundations. Second, they note the ongoing significance of discrimination and bias in the labor market, and the need for effective steps to counter these obstacles to economic mobility. "People of color and women are both overrepresented among low-wage workers. Echoing well-established trends, we found that much higher shares of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers are low-wage compared to white workers" (42). And third, they emphasize the need for regional strategies for economic and workforce development. They note: "A multitude of recent papers, speeches, and initiatives have highlighted structural problems in the labor market, and noted that too many workers will continue to be left behind absent dramatic policy change. Dani Rodrik and Charles Sabel formulate the issue in perhaps the starkest terms: "'Where will the good jobs come from?’ is perhaps the defining question of our contemporary political economy.'"" (43).

What is missing from this analysis of low-wage jobs? Unions, for one thing. The ten industries that represent about half of all low-wage workers have a low level of union representation. Retail sales workers and restaurant workers represent about 6.9 million low-wage workers, and collective bargaining is scarce in both sectors. If these workers -- and the other sectors on the list -- were unionized, it is unavoidable that wages would go up for these workers. But likewise, in line with the ongoing discussion of the prerequisites of significant economic reform, a strengthening of unions is also likely to lead to greater influence for political candidates and parties who support meaningful economic reforms.

Workers in the gig economy -- Uber and Lyft drivers and food delivery drivers, for example -- appear to fall in the low-wage category, though there are various estimates of Uber driver wages in the press. One careful report from 2018 by the Economic Policy Institute estimates after-expense hourly rates for Uber drivers at $11.77 per hour in 2018 (EPI, Lawrence Mishel, link). This amounts to a fulltime annual wage of about $24,000 -- without health benefits. ZipRecruiter reports wages for Amazon warehouse workers for every state, and hourly rates range from $11.56 (North Carolina) to $18.28 (Washington) (link). The threshold that Ross and Bateman define for low-wage status is adjusted by regional cost-of-living, but ranges from $12.54 (Beckley, WV) to $20.02 (San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA), with a national average of $16.03. By these criteria both gig workers and Amazon warehouse workers fall into the category of low-wage fulltime workers.

That provides some information about the low-wage workers. But the next segment of American working people are only a little better off. Here is a Bureau of Labor Statistics report on weekly earnings of fulltime workers in second quarter 2022 (link). The table illustrates the disparities in wages by race and gender that are mentioned by Ross and Bateman. Here are the data for median weekly wages (top of second quartile) for white men ($1,161), white women ($956), black or African American men ($953), and black or African American women ($840). These are data for individual wage-earners. Household income by decile can be found here, where median household income (CPI adjusted) is reported as $69,202. In 2020 the Federal poverty guideline for a family of four was $26,200, which means that the median household makes out its existence at an income level about 2.6x the poverty line. As noted in the previous post, the economic lives of people in households at or below the median income are likely to be precarious, anxious, and paycheck to paycheck.

So, again -- does the US have a working class, or are we overwhelmingly "middle class", suburban, and secure? The answer is evident: the majority of the US working population is involved in the wage-labor market, resulting in household incomes that barely suffice for the ordinary expenses of family living, and without significant possibility of accumulating savings or property. Further, 31.2 million people (11.5% of people under 65; link) lack health insurance -- another source of precarity, poor quality of life, and poor health.

So there is a very large population of working people in the US whose interests are not well served by the current system of employment and social services (including education and healthcare).

But here is the much harder question: does the American political system provide avenues of coordination, mobilization, and power that would permit this majority of the population to express its interests and needs in our electoral democracy? These tens of millions of workers in the low-wage and low-middle wage range -- are they in a position to develop political identities that could underlie effective demands for meaningful change in our economic arrangements? Or are we as a national population so dispersed, divided, and mutually antagonistic that political solidarity is inconceivable?

"A working class hero is something to be..."---John Lennon.

ReplyDeleteAs a low wage worker (paint sprayer) I figured out that I had better acquire rare but valued competencies if I’m to improve my standard of living. Sitting tight waiting for pay increases is a lot less effective than learning how to add more value through our work. With my new capabilities I was able to convince a new employer to pay me more. I kept doing this until I had saved enough over 15 years to pay for my sabbatical long enough to earn a masters degree. I then sought my own customers to pay me generously for my advice until I retired.

ReplyDeleteAfter reading your article, carefully, I considered my one line quip, deciding to add a few additional remarks. Your noting of division is crucial,in my view .People look at our fragmented systems and see no reason for optimism. This permeates every age group and is reason for hopelessness and the growing incidence of gun violence. Children, under the age of majority (16) were once rarely involved in gun crimes. Now, these incidents are common. Whether they have adult role models seems to make no difference. We have to be careful where we go, what we say, whom we have contact with.

ReplyDeleteFriends and family, in other parts of the world have it better. But, for how long we don't know.