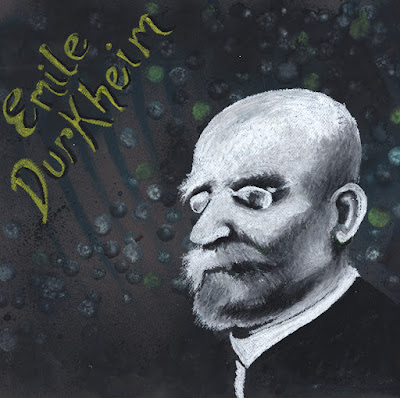

Emile Durkheim is celebrated for many achievements in the founding of the discipline of sociology, but most striking is his endorsement of the autonomy and irreducibility of the social realm to individual motivation, action, or psychology. "Social facts are things, irreducible to individual psychology." Durkheim was, we are often told, a social holist. This is a tantalizing and puzzling position. Here is a description of social facts offered by Durkheim in

Rules of Sociological Method:

Yet social phenomena are things and should be treated as such. To demonstrate this proposition one does not need to philosophize about their nature or to discuss the analogies they present with phenomena of a lower order of existence. Suffice to say that they are the sole datum afforded the sociologist. A thing is in effect all that is given, all that is offered, or rather forces itself upon our observation. To treat phenomena as things is to treat them as data, and this constitutes the starting point for science. Social phenomena unquestionably display this characteristic. (Rules, 69)

Social phenomena must therefore be considered in themselves, detached from the conscious beings who form their own mental representations of them. They must be studied from the outside, as external things" because it is in this guise that they present themselves to us. If this quality of externality proves to be only apparent, the illusion will be dissipated as the science progresses and we will see, so to speak, the external merge with the internal. (70)

Here, then, is a category of facts which present very special characteristics: they consist of manners of acting, thinking and feeling external to the individual, which are invested with a coercive power by virtue of which they exercise control over him. Consequently, since they consist of representations and actions, they cannot be confused with organic phenomena, nor with psychical phenomena, which have no existence save in and through the individual consciousness. Thus they constitute a new species and to them must be exclusively assigned the term social. It is appropriate, since it is clear that, not having the individual as their substratum, they can have none other than society, either political society in its entirety or one of the partial groups that it includes -- religious denominations, political and literary schools, occupational corporations, etc. Moreover, it is for such as these alone that the term is fitting, for the word 'social' has the sole meaning of designating those phenomena which fall into none of the categories of facts already constituted and labelled. (52)

Durkheim seems to be quite committed, then, to the full and complete separation between social facts and individual facts. His reasons are unconvincing, however.

Notice first that these points are entirely apriori. They derive from the idea -- almost Aristotelian in its dogmatism -- that each science must have a distinct and independent domain of things to study; and therefore sociology demands that social facts are distinct from the objects of study of another science -- psychology.

What are those supposed social facts? There are several that Durkheim refers to repeatedly: social conscience or morality; social habits and mores; laws and traditions; political arrangements; and social sentiments such as patriotism. In the simplistic understanding of Durkheim's ontology, these sets of norms, beliefs, values, and practices exist above individuals and constrain and direct their behavior. They cause events at the individual level, but they are not caused by individual-level events or conditions. This is an untenable holism, however. Further, there are important statements in Durkheim's writings that undercut this extravagant holism. For example, consider these comments from the second preface to the Rules:

Yet since society comprises only individuals it seems in accordance with common sense that social life can have no other substratum than the individual consciousness. Otherwise it would seem suspended in the air, floating in the void. (39)

Here he concedes the point that the social world consists only of individuals; but he wants to draw an analogy with the "emergence" of the physical properties of physical ensembles to support the idea that "social facts" are different in kind from individual facts:

The hardness of bronze lies neither in the copper, nor in the tin, nor in the lead which have been used to form it, which are all soft or malleable bodies. The hardness arises from the mixing of them. (39)

By analogy, he suggests that it is plausible to propose that social ensembles -- social facts -- possess properties different in kind from the properties of their parts -- the consciousness and representations of the individuals who make them up.

One is forced to admit that these specific facts reside in the society itself that produces them and not in its parts -- namely its members. In this sense therefore they lie outside the consciousness of individuals as such, in the same way as the distinctive features of life lie outside the chemical substances that make up a living organism. They cannot be reabsorbed into the elements without contradiction. since by definition they presume something other than what those elements contain. (39-40)

This line of thought is unconvincing, however. One giveaway is the phrase "by definition they presume something ...". We cannot learn something substantive about the nature of the world based on our definitions of "social facts" or our delineation of the "scope of sociology". Further, what are these qualitatively and ontologically new properties of the social realm? Social facts are said to be objective, independent, and coercive. They are objective because they persist over time. They are independent, perhaps, because they do not depend on any one individual's psychological content. And they are coercive because it is either impossible or inconvenient for individuals to reject them (for example, the conventions of money and debt). But these are peculiarly easy characteristics to explain in a microfoundational way -- more so even than the physical chemistry of the properties of a metal alloy. Once it is established that one should not spit into his dinner napkin at a formal meal -- a social fact -- the social fact is enforced through the fact that his dinner companions share the aversion, they express their disgust at his behavior, and they take him off future dinner guest lists. The microfoundations for this social norm are straightforward.

Consider another important point stemming from his view in Rules of the education of children:

Moreover, this definition of a social fact can be verified by examining an experience that is characteristic. It is sufficient to observe how children are brought up. If one views the facts as they are and indeed as they have always been, it is patently obvious that all education consists of a continual effort to impose upon the child ways of seeing, thinking and acting which he himself would not have arrived at spontaneously. (Rules, 53)

This passage refers to exactly the feature of social actors that I refer to as being "socially constituted" in my formulation of methodological localism (link). Children are brought to instantiate the beliefs, practices, behaviors, and values of the adults around them, and they in turn become the vehicles for the "social facts" represented by those beliefs and practices in the next turn of the wheel. It is straightforward, then, to provide the microfoundations of the idea that "the rules of polite French Catholic behavior" represent an objective social fact external to the particular beliefs of the individuals of society; once individuals have learned these rules, they become coercive for other individuals in the future. But -- contrary to Durkheim's rhetoric at various points -- there is no fundamental ontological separation between the "social fact of French politesse" and the psychological realities of French individuals. The individuals are shaped by their formative immersion in these rules as instantiated by their elders, and in turn go on to shape the behavior of others.

Durkheim is explicit in rejecting this microfoundational interpretation of social facts:

Thus it is not the fact that they are general which can serve to characterise sociological phenomena. Thoughts to be found in the consciousness of each individual and movements which are repeated by all individuals are not for this reason social facts. If some have been content with using this characteristic in order to define them it is because they have been confused, wrongly, with what might be termed their individual incarnations. What constitutes social facts are the beliefs, tendencies and practices of the group taken collectively. (54)

But this is a purely semantic point. Durkheim is insistent that French politesse is a social fact that is distinct from the psychological facts of French individuals because it is a feature of the ensemble taken collectively, not simply a conjunction of facts about individual psychology. It is what we might call a "category mistake" to confuse the two levels.

We might say anachronistically that Durkheim would have emphatically rejected the picture of the social world involved in Coleman's boat (link), and would also have rejected the idea that social statements require microfoundations. He might possibly have accepted ontological individualism (as the passage from the second preface suggests), but would have endorsed some kind of emergentism. Social characteristics are different in kind from individual psychological characteristics. But, as we have seen elsewhere, emergentism can be formulated in a weak and a strong version (link); and the strong version is fundamentally mysterious. The weak version maintains that higher-level properties are different from lower-level properties but can in principle be explained by the lower-level properties; the strong version denies that the higher-level properties can be explained by the lower-level properties at all. And this sounds very much like a sociological version of vitalism. Durkheim is not forced to defend strong emergentism.

In his substantive and insightful introduction to Rules Steven Lukes summarizes his own assessment of these issues in terms that still seem correct to me:

But the [holistic] view makes little sense as a positive methodological principle. Every macro-theory presupposes, whether implicitly or explicitly, a micro-theory to back; up its explanations: in Durkheim's terms, social causes can only produce these, rather than those, social effects, if individuals act and react and interact in these ways rather than those. (17)

These arguments seem to lead to a pair of conclusions. First, Durkheim's strenuous and repeated privileging of the independence of "social facts" should not be understood as a demonstration of the complete causal independence of social facts from individual representations; rather, his emphasis on this point seems to derive from his polemical goal of establishing sociology as an entirely independent science. But this is not a valid reason for drawing conclusions about ontology. Second, it is entirely possible to offer an account of the relationship between social-level and individual-level descriptions that joins them. Whether he would acknowledge the point or not, Durkheim's social ontology does not provide any basis for believing that claims about causation at the social level cannot be instantiated through some account of the actions and representations of individual actors at a time and place. We can put the point more strongly: Durkheim's sociology no less than Weber's or Marx's requires a theory of the micro-macro connection. Further, Durkheim sometimes appears to acknowledge this point (for example, in his treatment of education of children). Therefore Durkheim does not provide a basis -- philosophical, theoretical, or empirical -- for defending social holism.