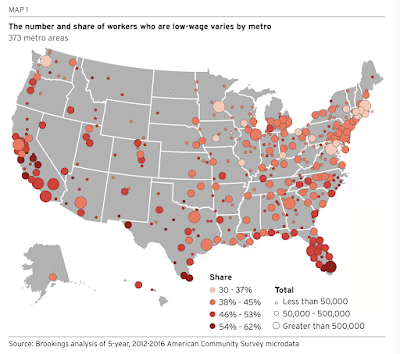

There is certainly a working class in the United States, and it is a majority of the population (persons who earn their livelihood through wage-paying employment). But it is highly fragmented, mostly in the service sector, unorganized, and often disinclined to believe in the possibility of serious social change. A recent Brookings research report by Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman on low-wage workers provides a clear analysis of the current situation (link). Their report is based on US Census data (American Community Survey 2012-2016). Low-wage workers make up 44% of the US workforce (53 million workers). Median annual earnings of low-wage workers was $17,950 in 2016.

Pages

Saturday, July 30, 2022

Is there a working class in the US?

There is certainly a working class in the United States, and it is a majority of the population (persons who earn their livelihood through wage-paying employment). But it is highly fragmented, mostly in the service sector, unorganized, and often disinclined to believe in the possibility of serious social change. A recent Brookings research report by Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman on low-wage workers provides a clear analysis of the current situation (link). Their report is based on US Census data (American Community Survey 2012-2016). Low-wage workers make up 44% of the US workforce (53 million workers). Median annual earnings of low-wage workers was $17,950 in 2016.

Monday, July 25, 2022

Gross economic inequalities in the US

An earlier post (link) highlighted the growing severity of inequalities of wealth and income in the United States, as well as Elizabeth Warren's very sensible "billionaire" tax proposal. According to a 2020 article in Forbes, "According to the latest Fed data, the top 1% of Americans have a combined net worth of $34.2 trillion (or 30.4% of all household wealth in the U.S.), while the bottom 50% of the population holds just $2.1 trillion combined (or 1.9% of all wealth)" (Forbes, link). That bears repeating: 1% of Americans own 30.45% of wealth in the United States, while the bottom 50% owns under 2% of wealth. Those disparities in wealth have worsened during the past two years of pandemic. The Forbes story notes that Elon Musk's wealth increased from $100 million to $240 million in the first eight months of 2020, and Jeff Bezos' wealth increased by $65 billion in 2020.

A recent story in the New Yorker on mega-yachts underlines the obscene imbalance that exists between the super rich and the rest of us. Evan Osnos' "The Floating World" offers a glimpse into the mega-luxury and consumption associated with super-yachts (link). Much of the world's attention to super-yachts has gravitated to the Russian oligarchs and the economic sanctions that have resulted in seizure of a number of multiple-hundred-million dollar ships around the world. But of course, it is not only Russian oligarchs who have captured their nations' wealth. Oligarchs and billionaires from the United States, Europe, the Middle East, and Central America are part of the same bleak picture.

The level of consumption on luxury involved in the world of super-yachts in the article is obscene in the original sense of the word; it is a conspicuous display of wealth that makes one sick. The idea that a single individual or family would have the financial ability to purchase a 500-million dollar ship (limited by maritime law to carrying only 12 guests and unlimited crew) is grotesque. (Osnos quotes a luxury yacht industry estimate that the annual cost of maintaining a mega-yacht is 10% of its purchase cost. So a half-billion dollar ship requires $50 million in annual maintenance.) And this grotesquerie is especially stark in a world where global and national poverty are persistent obstacles to free human development for the world's population and climate change imperils everyone. (Osnos notes that experts estimate that "one well-stocked diesel yacht is estimated to produce as much greenhouse gas as fifteen hundred passenger cars".)

It is impossible to describe the situation of wealth inequality in the United States as anything other than a "laissez-faire robber baron regime" of wealth creation and consumption. We functionally have no effective tax policy that constrains the accumulation of hundreds of billions of dollars by a small number of individuals and families.

Here is a very interesting video panel organized by the Brookings Institution on the current status of wealth-tax proposals (link). Especially interesting in the discussion is the emphasis on wider positive effects of a wealth tax, including a shift in political power and an enhancement of racial and gender equity.

So what about the rest of us -- the population falling below the 90th-percentile of income? Here is a graph of recent income-distribution data by select percentiles (link):

Several things are apparent from this graph of income distribution. (It is important to recall that the distribution of wealth is much more extreme than the distribution of income.) First, the median household income (50th percentile of households) is $67,463. This is just under 2.5 times the Federal poverty level for a household of four individuals. This income is pre-tax; so the monthly budget of the median household is roughly $4,000 per month. This is a very tight budget that must cover all expenses: housing, food, transportation, clothing, healthcare, and so on. It is clear that households at the 50th percentile are financially struggling, and are unlikely to be able to afford a mortgage on a house. These Americans are also likely to be unable to save significantly, including savings for future educational costs for their children. Second, the 99th-percentile household income is about 7.5 times the median household income. A family with over $500,000 household income has no month-to-month financial constraints; it is not difficult to save significant resources over time; and owning property for this household is entirely feasible.

To achieve an equal-opportunity society where there are no barriers to economic success that are the consequence of race, ethnicity, or gender disparities would obviously require tackling overt racism and sexism.

But true equal opportunity requires more than that. It involves addressing many other disparities that undermine worker productivity, such as unequal access to jobs, education, credit in the form of home mortgages and business loans, affordable child care, high-quality pre-Kindergarten, and senior care; inconsistencies in family leave and workplace policies and in treatment in the justice system; imbalances in access to healthcare and insurance; unequal exposure to damaging levels of environmental pollutants; and inadequate and unequal access to high-quality physical infrastructure, which is essential to maximizing economic efficiency.

Here is his conclusion:

The U.S. economic consequences of eliminating racial, ethnic, and gender inequalities are large, particularly for individuals of color and women. The total earnings in the nation would swell well beyond what they currently are, and the incomes of Black, Hispanic, and Asian workers would be substantially higher. The largest earnings gains would be experienced by non-Hispanic White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian women.

Whose wealth is it anyway? The libertarian laissez-faire ideology is that the "creators" of wealth are solely responsible for this wealth, and it morally and legally belongs to them. But a much more credible view is that a national economy is a vast and extended system of economic cooperation, with a substantial "social product" that should not be captured by a small number of strategically located actors. The term "rent-seeking" appears to apply perfectly here. There is also the familiar but spurious argument that vast inequalities are needed in order to generate incentives for productivity and innovation. This argument is spurious: first, much innovation comes forward from ordinary participants in economic activity who rarely see financial benefits from their innovations; and second, it is laughable to imagine that only the prospect of a $200-billion windfall would motivate an "entrepreneur" to his or her wild and crazy new ideas. Would the prospect of a billion-dollar windfall not work as an incentive? Would $100 million not work? Ha! The idea of the moral or economic inevitability of unlimited wealth accumulation is simply self-serving ideology.

In large strokes the Warren wealth tax proposal represents a moderate tax on the super-rich; and it could have a very large impact on a range of issues of political stability, economic equity, and equality of opportunity that are crucial for the future of our democracy.

Monday, July 11, 2022

English socialism

What were the social conditions that led many English intellectuals in the 1930s to engage in fundamental critique of the society in which they lived? Why was social criticism so profound and sustained in Britain from the time of Carlyle and Engels to the surge of English socialism in the 1930s?

The answer, of course, is the harshness and cruelty of capitalism and the rapid industrialization and slummification of cities like Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow, and London in the 1840s and the century that followed. It was the perfectly visible immiseration of British working people, and the growing conviction that this was a systemic consequence of the new economic order, that inspired observers as politically diverse as Carlyle and Engels to write their descriptions and denunciations of the emerging economic system (link, link). And it was this perception of systemic exploitation and ruin that led critics to try to imagine a social and economic system that would make those evils impossible.

These critiques were not primarily driven by ideology; they were not driven by an antecedent political program. Instead, many of these social critics were conducting what we might today call "micro-sociology", investigating and documenting the modes of life found in particular communities. The programs for radical change came next. Radicalism did not create the conditions of poverty, bad health, and demoralization that Carlyle, Engels, or Orwell described; rather, the range of socialist visions that appeared were responses to the social dysfunctions that were entirely visible in 19th- and 20th-century capitalism.

If one witnesses the debris and death of a plane crash, one is saddened for the loss of life, but it is possible to think of the crash as a tragic accident. But when one reads of the extraordinary rates of fatal and maiming accidents in the coal-mining industry, the "unfortunate accident" view is not tenable. The high rate of accidents observed is systemic, deriving from the management's failure to invest in appropriate safety equipment and processes as a means of propping up profits as well as the utter lack of effective state regulation of mine safety.

Likewise, a single impoverished family is a sad event; whereas a whole impoverished class is systemic and must be treated as such. A social order that consigns 40% of its population to extreme poverty, illiteracy, and poor health is an unacceptable social order. It must be changed. This was the conviction that was shared by a broad swath of observers of English society in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But what form might that change take? That was the question that faced social critics at the end of the nineteenth century. And the question continued through the Great Depression into the 1930s. For many critics, the answer was some form of socialism.

Consider George Orwell and his work of documentary journalism, The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). The book was commissioned by the Left Book Club, organized by Victor Gollancz, Harold Laski, and John Strachey, to investigate unemployment in the Midland industrial regions. The first half of the book is based on careful and exact observation of the conditions of life and work of the coal miners and their families in industrial northern England. (Wigan is roughly midway between Manchester and Liverpool.) The conditions of work and living that Orwell describes are horrible and dehumanizing. The work of coal mining was highly dangerous, with high rates of injury and death; the pay was poor, with many deductions; the work was physically taxing in the extreme (Orwell describes the harrowing trudge from the "cage" to the coal face in terms that are almost Promethean in their physical demands); and the working day involved manually moving tons of coal from the coal face to the conveyer belt by miners crouched on their knees. Living conditions were awful as well, both in the central slums and in the scarce and shoddy new housing slowly being built by the municipalities. Sanitation was primitive, living spaces were damp and bug-infested, and every lodging was severely over-crowded. And work was scarce, with high rates of unemployment in every family. Orwell conveys great respect for the men and women whom he meets during his time in the industrial north, but he is also clear-eyed about the dehumanization created by poverty, malnutrition, and precarious and squalid housing.

The critique of the systemic immiseration created by capitalism raised the urgent question of change. But it doesn't determine the answer. Can the worst features of capitalism be reformed? Can the effective political power of working people be increased and brought to bear in support of measures like unemployment insurance, retirement security, and access to education and healthcare? Can extreme economic inequalities be managed through tax policies? That is, are there possible adjustments to capitalist ownership that retain the main features of capitalism but ensure the fundamental interests of working people? We might describe this as reform of laissez-faire capitalism in the direction of "capitalism with a human face", welfare capitalism, or social democracy. Roosevelt's New Deal represented ambitious efforts along these lines, including programs to address mass unemployment (the Works Progress Administration) and old-age poverty (the Social Security Administration). Marx and his followers in the serial Internationals argued that piecemeal reform of capitalism was not possible -- "capitalist ownership implies capitalist dictatorship" -- but that is simple dogma. Perhaps strong labor unions and a progressive political party can institute and preserve social-democratic reforms within the broad confines of a market economy.

Second, if the critic is persuaded that private ownership and management of industrial firms is itself the cause of immiseration -- because owners are under constant profit imperatives of cost reduction, leading to negative pressure on wages and strong resistance to taxation for social programs -- then a second broad avenue for reform is democratic socialism. If private ownership of industry leads to immiseration, then reformers are led to consider social ownership of some kind. Here the slogan might be: democratic institutions govern the state, and a system of social ownership owns and manages productive wealth. Here again there are multiple scenarios to imagine. One possible arrangement of social ownership might involve municipal ownership, much as utility companies were once owned by public authorities. Another possible arrangement is workers' cooperatives (link, link), in which the employees of a firm are also the owners. Again, this is not an unknown arrangement even within an advanced capitalist economy. These alternative systems of social ownership can be described as varieties of democratic socialism, with distributed ownership of the means of production.

Yet another arrangement that might capture the purposes of democratic social control of the economy and decent outcomes for all members of society is the system that John Rawls describes as a property-owning democracy (link). On this view, political institutions embody democratic values of maximal equal liberties and democratic decision-making. And economic institutions are essentially arranged around "mutual funds" owned by all citizens that own enterprises and are subject to democratic oversight by their shareholders (citizens). Rawls writes:

Both a property-owning democracy and a liberal socialist regime set up a constitutional framework for democratic politics, guarantee the basic liberties with the fair value of the political liberties and fair equality of opportunity, and regulate economic and social inequalities by a principle of mutuality, if not by the difference principle. (Justice as Fairness, 138)

All of that said, Orwell was not Keynes; he was not a systematic thinker about social and economic institutions. If we want a detailed, plausible, and workable version of a democratic-socialist Britain, we will have to look elsewhere. Rather, Orwell was a social observer who was passionately committed to the value of the full human development of all members of society; secure equality of opportunity; constrained levels of economic inequality; and full embodiment of political and individual rights and liberties. What he observed in the slums and coal mines of Yorkshire and Lancashire was a human reality at a vast distance from full human development and the equal worth of all members of society. What he demanded was a social, economic, and political order that ended these inexcusable conditions for a large fraction of British society.

(Here is a post that offers a critique of contemporary conditions of work in a large American industry -- Amazon fulfillment centers (link), and the dehumanization and economic stagnation that this business model implies for its workers. One can only hope that union organizers will become increasingly successful at Amazon warehouses.)

Thursday, July 7, 2022

HB Acton's version of Marxism

H. B. Acton gained celebrity with the publication of Illusion of the Epoch in 1955, supposedly as a serious philosopher's even-handed exposition of the philosophy expressed in Marx's writings. Acton was not an especially influential philosopher, and he certainly does not stand in the first ranks of post-war British philosophy. He taught philosophy at the London School of Economics, Bedford College (London), the University of Edinburgh, and the University of Chicago. (It is difficult to find biographical information about Acton; for example, where did he complete his doctoral studies, and who were his primary influences?) And the book misses much that is of interest in Marx in the interest of tying Marx to Hegel at one end and to Lenin and Stalin at the other.

It seems likely that much of the celebrity of the book derived from its title, "Illusion of the Epoch", which seemed to imply that Acton would unveil Marxism as the illusion of the epoch of the 1930s through 50s. But he never explains the title, and in fact it is borrowed from the German Ideology in an entirely different context. The conservative foundation and publisher Liberty Fund republished the book in 1962, and it is easy to speculate that "the Marxist illusion" was a major selling point of the book to the New Liberty editorial board. Certainly Acton's book falls far short in two crucial ways: it is not a credible interpretation of Marx's philosophical ideas, and it does not expressly say why Marxism is an illusion. We can guess, but the book doesn't provide an argument or explanation.

Most fundamentally, Acton's premise in Illusion was ... illusory. He began with the assumption that the philosophy expressed in Marx's writings is fully and adequately expressed in the writings of Lenin and Stalin; in fact, he treats "Marxism" as "Marxist-Leninism". As a result, he vastly overestimates the importance of "dialectical method" in Marx's writings -- let alone the coherence or importance of "dialectical materialism" for Marx, since this is not a phrase that Marx used anywhere in his corpus. (The phrase was coined by a follower of Marx four years after his death, in 1887.) This takes us off on a wild-goose chase in the book, since the reader came with an interest in Marx's thinking as a philosopher, and what the reader got instead was a rowboat piloted by Engels, Lenin, and Stalin. But if -- as I believe -- Marx put aside the philosophical claptrap of Hegelian dialectics when he turned to thinking seriously about history and political economy, then the elaborate exposition that Acton provides interpreting Hegel on the one hand and Lenin on the other hand is entirely useless when it comes to interpreting Marx's philosophical and theoretical thinking.

The superficiality of Acton's treatment of Marx is evident throughout the book. Here are a few broad, sweeping, and silly statements:

We have now seen that, on the Marxist view, everything is changing, and that periods of gradual change are interspersed with sudden changes in which new types of being come to birth. Marxists regard it as a merit of their theory that it is also capable of explaining why nature changes at all. (85)

We have not so far discussed the proposition that all things are ‘‘organically connected with, dependent on, and determined by each other.’’ That things are not so connected is the thesis of ‘‘metaphysics,’’ in Engels’ sense of the word. What sort of unity of the world, then, do Marxist philosophers assert? It is easy to see that, on their view, nature is one, inasmuch as it is fundamentally material—there is nothing in nature that is not based in matter. (91)

These are certainly not Marx's views. Whether it is a credible interpretation of Engels' view or Lenin's view, I'm not sure. But Engels and Lenin are not Marx. And it is hard to see how a person who has read Capital could seriously suggest that these views underlie Marx's effort to understand capitalism.

Part I of Illusion is therefore fundamentally irrelevant to Marx's approach to understanding the contemporary world (capitalism). What about Part II, where Acton turns to "historical materialism"? Here Acton adopts another red herring -- the idea that historical materialism is meant as a serious effort to explain religion and religious consciousness and ideology (100). These are highly subordinate concerns for Marx, and he gives little specific attention to how material social institutions influence or "determine" ideological frameworks. Rather, Marx is interested in explaining the large systemic changes in history.

Finally, after dozens of pages, Acton arrives at a sensible statement of Marx's theory of historical materialism:

The main point, then, of the Materialist Conception of History is as follows. The basis of any human society is the tools, skills, and technical experience prevalent in it, i.e., the productive forces. For any given set of productive forces there is a mode of social organization necessary to utilize them, i.e., the productive relationships. The sum total of productive relationships in any society is called by Marx its ‘‘economic structure.’’ This, he holds, is the real basis on which a juridical and political superstructure arises, and to which definite forms of social consciousness correspond. Radical changes in the basis sooner or later bring about changes in the superstructure, so that the prime cause of any radical political or moral transformation must be changes in the productive forces. In effect, the idea is that human society has a ‘‘material basis’’ consisting of the productive forces and associated productive relationships. This is also called the ‘‘economic structure.’’ This, in its turn, determines the form that must in the long run be taken by the legal and political institutions of the society in question. Less directly but no less really dependent on the economic structure of society are its moral and aesthetic ideas, its religion, and its philosophy. The key to the understanding of law, politics, morals, religion, and philosophy is the nature and organization of the productive forces. (128-129)

This is a reasonable statement of Marx's general theory of historical materialism; but it is no more than a close paraphrase of the summary offered by Marx in the preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859) (link). No subtle reinterpretation of Marx's meaning is required; Acton's paragraph simply paraphrases the parallel text in the preface to the Contribution. And, once again, Acton defeats his own goal (to interpret Marx's philosophical ideas) by turning immediately to Stalin's and Lenin's counterpart ideas.

In Part III Acton turns to what he calls "Marxist Ethics". Here again, much of the discussion has to do with what Lenin and Stalin had to say about ethics. But, as above, this is a different subject. Here is an example:

It will be remembered that in Chapter I of Part One of this book I called attention to the fact that one of Lenin’s arguments against phenomenalism was that phenomenalism is a form of idealism, that idealism is a disguised form of religion, that religion is dangerous to communism, and that therefore phenomenalism should be rejected. Basic to this argument is the assumption that it is legitimate to reject a philosophical theory on the ground that it appears to be a hindrance to the victory of the proletariat under Communist Party leadership. In still more general terms, Lenin’s argument assumes that it is legitimate to reject a philosophical theory on the ground that it appears to conflict with a political movement supposed to be working for the long-term interests of mankind. (191)

As a treatment of Marx's thought, there is almost nothing to recommend in Acton's book. So why dwell on a book that has so little philosophical insight into its subject matter? Because this book is one of the texts from the 1940s and 1950s that set the terms for philosophers' understanding of Marx; and because the book is a bumbling trivialization of Marx's ideas. A much better introduction and overview of Marx's thought was provided by Isaiah Berlin in 1939 in Karl Marx: His Life and Environment. And Berlin was a much more penetrating philosopher than Acton. (Using Google NGram tool, it emerges that book mentions of Isaiah Berlin are more than 1000 times more frequent than for Harry Acton since 1950.) Even Sherwood Eddy's introduction to Marx in the 1934 volume The Meaning of Marx, short though it is, does a much better job of introducing the reader to Marx's central ideas (link). On the other hand, if we want to understand why Stalinism was a moral catastrophe, we would do better to read The God That Failed, including autobiographical essays by Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Richard Wright, Andre Gide, Louis Fischer, and Stephen Spender. (Richard Wright's essay is particularly powerful.) These personal statements make much more vivid the appeal of Marxism for intellectuals concerned about social justice in the 1930s, and shed much more light on the totalitarian disaster that doctrinaire Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism led to at every level -- from Moscow and Kiev to Berlin to Milan to Chicago.

Acton's book reflects the very low level of interest or knowledge that analytic philosophers of the 1950s had in Marx as an original thinker, as opposed to a talisman and predecessor for totalitarian communist regimes in the USSR and its satellites. A return to serious, critical study of Marx would have to wait for another generations of philosophers in the 1980s.

Sunday, July 3, 2022

Sidney Hook's theory of education in a democracy

Philosopher Sidney Hook is best remembered for his debates with other philosophers and engaged political figures about Marxism and Communism (link). My interest here is in a different part of his work after World War II, his philosophy of education. Hook was a student of John Dewey, the author of Democracy and Education, but ultimately Hook had more to say about what educational values ought to guide a modern university than did Dewey. Much of Hook's theory was expressed in Education for Modern Man, published in 1946 and republished and extended in 1963. The book has a striking degree of relevance today in the context of debates over curriculum both inside universities and outside. What is the value of a liberal education? Is a "Great Books" curriculum a good basis for a liberal education in a democracy? How should the content of a liberal education be made compatible with "education for a career"? And what ideas are out of bounds within a university classroom? Hook had trenchant answers to all of these questions. (Here is an earlier post on the question of how to define the goals of a liberal education; link.)

Let's begin with Hook's assessment of the state of liberal education in post-World War II America.

Whatever a liberal education is, few American colleges offer it. Despite the well advertised curricular reforms in a few of our leading colleges, by and large the colleges of the country present a confused picture of decayed classical curriculums, miscellaneous social science offerings, and narrowing vocational programs -- the whole unplanned and unchecked by leading ideas. What one finds in most colleges cannot be explained in terms of a consciously held philosophy of education, but rather through the process of historical accretion. The curriculum of a typical college is like a series of wandering and intersecting corridors opening on rooms of the most divergent character. Even the cellar and attic are not where one expects to find them. (4)

Hook proposes that educators need to think more carefully about the purpose and goals of a college education.

The discussion will revolve around four generic questions:

- What should the aims or ends of education be, and how should we determine them?

- What should its skills and content be, and how can they be justified?

- By what methods and materials can the proper educational skills and content be most effectively communicated in order to achieve the desirable ends?

- How are the ends and means of education related to a democratic social order?

A satisfactory answer to these questions should provide a satisfactory answer to the problem of what constitutes a liberal education in modern times. (6)

- Education should aim to develop the powers of critical, independent thought.

- It should attempt to induce sensitiveness of perception, significantly associated with the different receptiveness to new ideas, imaginative sympathy with the experiences of others.

- It should produce an awareness of the main streams of our cultural, literary, and scientific traditions.

- It should make available important bodies of knowledge concerning nature, society, ourselves, our country, and its history.

- It should strive to cultivate an intelligent loyalty to the ideals of the democratic community and to deepen understanding of the heritage of freedom and the prospects of its survival.

- At some level, it should equip young men and women with the general skills and techniques and the specialized knowledge which, together with the virtues and aptitudes already mentioned, will make it possible for them to do some productive work related to their capacities and interests.

- It should strengthen those inner resources and traits of character which enable the individual, when necessary, to stand alone. (55)

Saturday, July 2, 2022

A 1934 debate about communism among American philosophers

The appeal of Marxist socialism -- communism -- as an alternative to the consumerism, inequality, and exploitation of European and American capitalism was a powerful draw for many intellectuals in the 1930s, especially in the context of the great Depression and widespread crisis and deprivation of the 1930s. This interest extended to many prominent American philosophers. It is a credit to philosophy that these philosophers took on the great issues of the day and engaged seriously with them.

1934 was an especially intense time for intellectual and political debate between defenders of liberal democracy and advocates for some version of communism. The Depression was in full swing, and there was a widespread view in Britain, France, and the United States among intellectuals that capitalism was bankrupt -- incapable of solving the social problems it created and confronted. On the other side, the enormous failures of Stalinist Communism were not yet as visible in the west in1934 as they would be in 1954. The Moscow Show Trials were still five years in the future, the Holodomor was not yet widely known in the west, and -- at least in its propaganda image -- Soviet economic planning had succeeded in transforming a backward society into a rapidly developing modern industrial economy.

A particularly interesting document from 1934 is a symposium called The Meaning of Marx (link) including contributions by Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, Morris Cohen, Sidney Hook, and Sherwood Eddy. All of the contributors except Eddy are leading philosophers in the analytic and pragmatist traditions of philosophy, and their comments and reflections on communism as a social-political system are highly interesting.

Sherwood Eddy and Sidney Hook frame the symposium with articles entitled "An Introduction to the Study of Marx" (Eddy) and "The Meaning of Marx" (Hook). Dewey, Russell, and Cohen offer brief essays on the topic, "Why I am not a Communist", and Sidney Hook has the final word with an essay called "Communism without Dogmas". This period of debate is much more interesting and substantive than the vitriolic animosities expressed in the 1950s under the conditions of McCarthyism, because each of these authors makes a serious and sustained effort to make sense of the historical events through which they are living. (In 1937 Dewey and Hook were also actively involved in supporting Leon Trotsky against Stalin's accusations following the Moscow show trials of 1936.)

Sherwood Eddy

Sherwood Eddy is not a familiar name, but he was a prominent Protestant educator and missionary, educated at Yale and Princeton Theological Seminary. What is striking about Eddy's essay is the unstinting admiration he expresses for the ideology and values of Soviet Communism. Eddy's interpretation of social change remains "religious" in a sense; he understands Communism as a unifying belief system capable of motivating the masses of the population.

Russia has achieved what has hitherto been known only at rare periods in history, the experience of almost a whole people living under a unified philosophy of life. All life is focused in a central purpose. It is directed to a single high end and energized by such powerful and glowing motivation that life seems to have supreme significance. It releases a flood of joyous and strenuous activity. The new philosophy has the advantage of seeming to be simple, clear, understandable, all-embracing and practical. (2)

Further, he contrasts the ideological unity and purity of Soviet society with the degeneration of values in western capitalist society:

At the end of the essay Eddy summarizes points of agreement and disagreement with Marx; most important is this point:

I. I do not believe that violent revolution is inevitable, nor do I believe that it is desirable in itself as Marx almost makes it. When once violence is adopted as a method in an inevitable and "continuing revolution," when to Marx's philosophy is added Lenin's false dictum that "great problems in the lives of nations are solved only by force," most serious consequences follow wherever communism is installed under a dictatorship or prepared for by violent methods. This shuts the gates of mercy on mankind. In Soviet Russia all prosperous farmers are counted kulaks, and the kulak becomes the personal devil or scapegoat of the system, as does the Jew in Nazi Germany. Intellectuals and engineers are all too easily accused of deliberate sabotage, of being "wreckers," class enemies, etc. When this philosophy--that great problems are solved "only by violence"--is applied, then trials, shootings and imprisonment follow in rapid succession. Hatred and violence mean wide destructive and incalculable human suffering. (27)

Thus, though I acknowledge my real debt to Marx, I do not count myself a Marxist. I have stated elsewhere: the reasons which would make impossible my acceptance of the system as practised in Soviet Russia under the dictatorship: Its denial of political liberty, the violence and compulsion of a continuing revolution, and the dogmatic atheism and anti-religious zeal required of every member of the Communist Party. (29)

Here he draws out precisely the implication of totalitarianism contained in Stalin's version of the "dictatorship of the proletariat". The war on the kulaks -- the Holodomor -- was going on as this symposium took place (1933-34) (link).

Sidney Hook

Sidney Hook was a well-known philosopher, with a political commitment to radical change and a willingness to defend Communist ideas in the 1920s and early 1930s. He became anti-Communist and anti-Stalinist beginning in 1933 and broke fully from the Communist International by 1939, but remained on the left as a democratic socialist. Hook came to be regarded by some on the left as a renegade and new conservative, but Tony Judt disagrees strongly with that view:

He became an aggressively socialist critic of communism. The “aggressively socialist” is crucial. There’s nothing reactionary about Sidney Hook. There’s nothing politically right-wing about him, though he was conservative in some of his cultural tastes—like many socialists. Like Raymond Aron, he was on the opposite side of the barrier from the sixties students. He left New York University disgusted with the university’s failure to stand up to the sit-ins and occupations—that was a very Cold War liberal kind of stance. But his politics were always left of center domestically and a direct inheritance from the nineteenth-century socialist tradition. (Judt, Thinking the Twentieth Century, 226)

So what was Hook's position in 1934? He believed that it was valuable to distinguish between Communism (the specific version implemented after the Russian Revolution) and communism (the ideal theory implied by Marx's writings on post-capitalist society). Hook's goal in "The Meaning of Marx" is to express what he thinks Marx's writings actually imply about "communism". And he believes, even in 1934, that Stalinism was a cruel perversion of that vision of the future, but that Marx's own conception was the correct pathway for modern people to follow.

Here is the first premise of Hook's view:

Marxism [urges] social action which aims by the revolutionary transformation of society to introduce a classless socialist society. (33)

What is a "classless society"?

The abolition of private ownership of the social means of production spells the abolition of all economic classes. (38)

This point reflects a double-pronged theory on Marx's part: ownership confers massive economic advantage to one group over another, and that advantage is transformed into the political power needed to sustain the class system itself against the protests of the under-class.

Hook then turns to the political implications of this socio-economic analysis of capitalism. How can the working class gain political power over the propertied class? His account has three features -- militant action by the masses of workers for improved conditions, coordination with "intermediate and subordinate groups" to change the existing order, and to "destroy the myth of the impartiality of the state" in order to effectively demand social and political revolution (47).

So what about dictatorship and democracy in Marxist socialism? Hook argues that Marx's conception involves a genuine version of democracy that is different from liberal democracy: "proletarian democracy".

Against the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, Marx opposed the ideal of a workers' or proletarian democracy. His criticism of political democracy in bourgeois society is that it is a sham democracy for workers--a sham democracy because, no matter what their paper privileges may be, the workers cannot control the social conditions of their life.

In the nature of the case, a workers' democracy--based upon collective ownership of the means of production--does not involve democracy for bankers, capitalists and their supporters who would bring back a state of affairs which would make genuine social democracy impossible. (49)

How is proletarian democracy different from dictatorship?

According to Marx, in at least two important respects. First, it expresses the interests of the overwhelming majority of the population, and by providing a social environment in which human values rather than property values are the guiding principles of social control permits the widest development of free and equal personality. Second, as the democratic processes of socialist economy expand and embrace in its productive activities the elements of the population which were formerly hostile, the repressive functions of the estate gradually disappear. (49).

This paragraph has the tragic ring of utopian optimism about the "withering away of the state", and observers of the logic of Stalinist repression would note -- this expectation of gradual democratization is absurdly unlikely. It sounds like an op-ed piece in the Daily Worker. Hook is strongly opposed to the dictatorship of the party (50); but the logic of power demonstrates that what he describes is a fairy tale. And later in his career, it is doubtful that Hook would have claimed or expected such a benign development. I will return to Hook's views later.

Bertrand Russell

Russell responds directly to the question, "Why I am not a Communist'. He makes it clear that by "Communist" he means "a person who accepts the doctrines of the Third International" (52) -- that is, a Stalinist. His reasons are stated succinctly. He denies "historical necessity" to any particular process of historical change -- including the necessary triumph of socialism over capitalism. He finds the theories of value and surplus value in Marx to be indefensible. He rejects the concept of "heroic infallibility" of any individual -- whether of Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, or Stalin. Unlike Hook, he takes the "dictatorship of the proletariat" at its plain meaning and rejects it because it is fundamentally anti-democratic. As a sociological fact he observes that Soviet Communism is highly repressive of liberty -- freedom of thought and expression -- and he rejects it on that basis as well.

He also has several more minor objections. Marx glorifies manual work over intellectual work. "Class war" is unlikely to succeed, and politics should proceed through persuasion rather than violence. Communism is grounded in hate, and hate is not a basis for social reconciliation. The claim that we must choose between communism and fascism is a wholly false choice; there is a third alternative -- liberal progressive democracy.

John Dewey

John Dewey's response to the question is similar to Russell's. Soviet Communism is authoritarian, repressive, and dogmatic. The Communist view of history is deterministic and monistic. The primacy Marxism gives to class conflict over-estimates this particular economic source of conflict within society Worse, the threat of proletarian uprising is likely to bring about fascism. Communist politics -- the behavior of the Communist state and its functionaries -- rely on lies, deception, and betrayal. And social change created only through violence by one group against another cannot succeed.

Were a large scale revolution to break out in highly industrialized America, where the middle class is stronger, more militant and better prepared than anywhere else in the world, it would either be abortive, drowned in a blood bath, or if it were victorious, would win only a Pyrrhic victory. The two sides would destroy the country and each other. (56)

Dewey's response gives the impression of a person who has reflected seriously both on history and on the pro's and con's of communism. His rejection of communism is fully considered and reflective.

Morris Raphael Cohen

Morris Cohen too gives powerful intellectual and personal reasons why he is not a communist. He finds Marx's political economy highly illuminating; but the associated theory of revolution and socialism is unacceptable to him. Most importantly, the experience of Soviet Communism is a humanly appalling example of repression and dictatorship. Cohen makes a very interesting historical point: uprisings by single groups almost always lead to disaster, massacre, and oppressive reaction (58). Profound social change requires a high level of social concurrence. He draws attention to the social violence that the USSR is brought to impose:

To this day the Communist regime dare not declare openly in favor of nationalizing the land. Their system of cooperatives is frankly an attempt--and I do not believe it will be a successful attempt--to evade the peasants' unalterable opposition to communism so far as their own property is concerned. (59)

(Here again -- the collectivization of farmland in Ukraine and the horrendous war of starvation against the kulaks was just beginning in 1933-34 in the USSR.)

Rather than harsh dictatorial imposition of the will of one class over another, Cohen offers the view that real social change requires cooperation among social groups:

If the history of the past is any guide at all, it is that real improvements in the future will come like the improvements of the past, namely, through cooperation between different groups, each of which is wise enough to see the necessity of compromising with those with whom we have to live together and whom we cannot or do not wish to exterminate. (60)