The United States has a long history of racism against African-Americans, at multiple levels. At the level of individuals, we have a history of negative attitudes, stereotypes, fears, and antagonisms that are built into the social consciousness of white men and women about African-Americans. Racist attitudes about “genetic inferiority”, crime, and other negative stereotypes have persisted since the slave period. At the level of behavior, institutions and individuals in “majority society” discriminate against African-American men, women, and children. The code of inter-racial behavior embodied in the Jim Crow epoch has continuing relevance to contemporary society, and discrimination in employment and other socially important opportunities persists. And then there is “structural racism” or “institutional racism” — the persistence of patterns of disparity and disadvantage for African-American individuals and families that seem to result from the workings of the institutions themselves. Residential segregation and its consequences provide a clear illustration of structural racism, and the persistence of health and longevity disparities by race illustrates the deadly seriousness of these patterns of unequal treatment. (Here is an earlier post on racial disparities.)

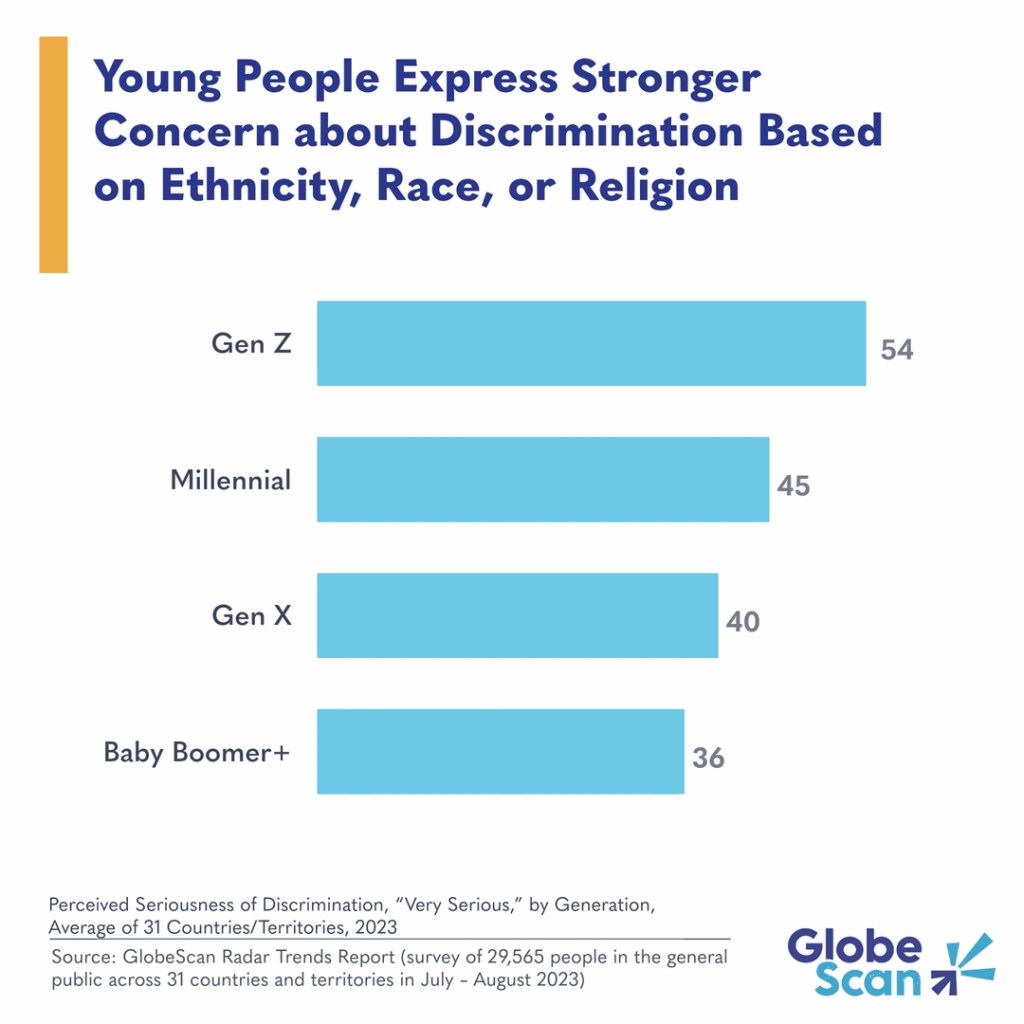

Observers have recognized for decades that American society needs to change in order to eliminate these facts of racism and substantive disparity of outcomes. But what kinds of change are called for? There is a comforting theory of change that seems to have some empirical basis. It is the idea that each cohort of Americans has become less racist and more tolerant of diversity than its predecessor cohort. On this account, the “silent generation” (1928-1945) had more explicitly racist attitudes than the baby boomers (1946-1964), Gen X (1965-1980), and Gen Z (1996-?). Each successive cohort was more accepting of racial diversity than its predecessor. This narrative suggests that racism and its legacy will die out as the more tolerant generations replace their less tolerant predecessors. GlobeScan, a global public opinion research organization, published the results of a brief survey on this topic in 2023 (link):

This report offers an empirical snapshot of the change across generations that is evident in some public opinion surveys: that concern about racial discrimination has steadily increased across recent generations of people. This is a comforting storyline for anyone who cares about an inclusive multicultural democracy. But Christopher DeSante and Candis Watts Smith argue in Racial Stasis: The Millennial Generation and the Stagnation of Racial Attitudes in American Politics (2020) that the storyline is fundamentally incorrect.

DeSante and Smith do not dispute that the generations since the 1940s have indeed experienced a shift in racial attitudes away from overt and explicit “biological racism”. Generations since the baby boom of the 1950s have internalized more “race-neutral” ways of describing current realities. And they have expressed rising discomfort with the fact of continuing racial discrimination. But these generations — GenX, Millennials, and GenZ in particular — appear not to have moved forward to the logical conclusion — the need for supporting the policy changes that would be effective in addressing the continuing realities of racial discrimination. This is the “stagnation and stasis” to which DeSante and Smith refer in the title of the book: progress on ending racism appears to have stalled.

The heart of their argument involves the question of how to measure “racist attitudes” among individuals. For several decades the primary tool of social-psychological measurement of racial attitudes has been based on the concept of “racial resentment” or symbolic racism. Survey questions were designed to elicit the subject’s level of resentment, fear, or antagonism towards members of another race. DeSante and Smith argue that this approach is no longer satisfactory as a measurement tool. They maintain that racism is inherently multidimensional, involving emotions and cognitive assumptions and frameworks, and a satisfactory measure needs to permit observation of several of these dimensions in the subjects of a survey. Instead they offer a four-dimensional framework that they call FIRE (Fear, Institutionalist Racism, and Empathy), and they use a set of survey questions that allow measurement of each dimension. These questions are designed to capture the emotional and cognitive components of “attitudes about race” among individuals in a racially mixed society.

Their measurement tool elaborates on these four questions:

-- I am fearful of people of other races.-- White people in the US have certain advantages because of the color of their skin.

-- Racial problems in the US are rare, isolated situations.

-- I am angry that racism exists. (DeSantes and Smith 2020: 227)

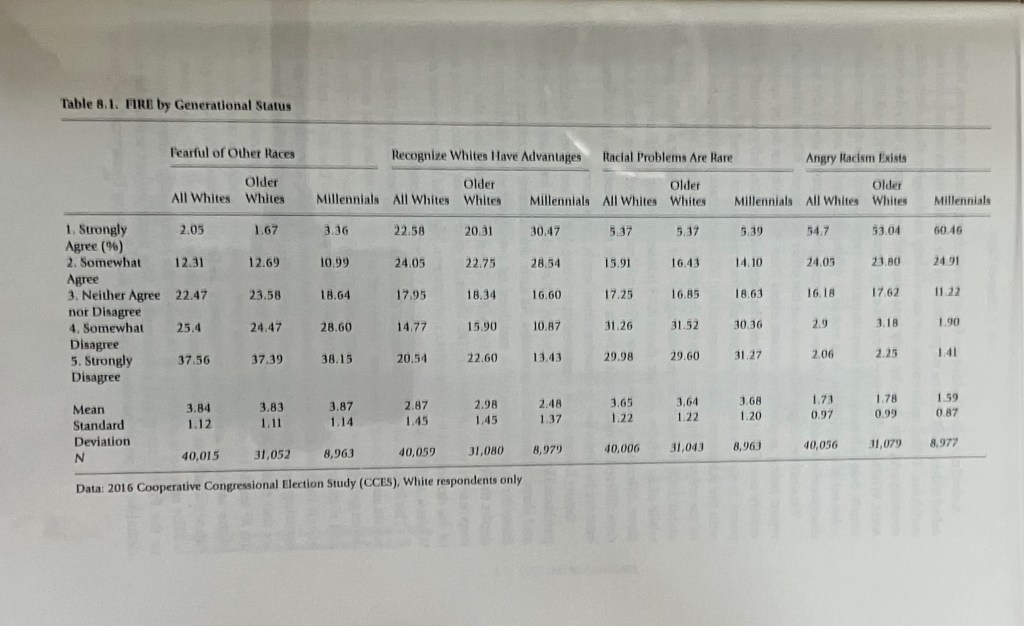

The questions are borrowed from several other survey instruments and are validated using statistical tools of consistency and predictive value. Here are the results of using these questions on the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (White respondents only).

The results are striking. Millennials are no less “racist” on average than the population of older whites on each of these measures. Here are the mean values for each question:

- -- “Fearful of other races” 3.83 vs. 3.87

- -- “Recognize whites have advantages” 2.98 vs. 2.48

- -- “Racial problems are rare” 3.64 vs. 3.68

- -- “Angry racism exists” 1.78 vs. 1.59

On average, Millennials demonstrate the same level of racist attitudes as older whites. The pattern is somewhat different when we compare “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” responses to the four questions.

- -- “Fearful of other races” 14.36 vs. 14.35

- -- “Recognize whites have advantages” 43.06 vs. 59.01

- -- “Racial problems are rare” 21.28 vs. 19.59

- -- “Angry racism exists” 76.84 vs. 85.37

There are two significant differences in these “agree” responses. Millennials are more likely to agree that “whites have advantages” and agree more frequently that they are “angry racism exists”. Millennials are more likely to disagree or strongly disagree that they are “fearful of other races”. But overall, DeSantes and Smith argue that these differences are small, indicating that little change has occurred between the generations born before 1981 and the Millennials. Millennials have abandoned “old-fashioned racism” but have not advanced much further. Here is their summary statement:

Generally speaking, our results in this chapter also highlight the issue of racial stasis, as signs of the countervailing forces remain visible. For instance, White millennials do present more progressive attitudes. Compared to their predecessors, they are more likely to express anger about racism and more likely to acknowledge their privilege. But we also found that nearly one in five White millennials (20 percent) simultaneously feels angry that racism exists and does not believe Whites have advantages because of the color of their skin…. Ultimately we have a large number of walking contradictions in American society that are helping to produce and perpetuate ongoing racial inequities through their political stances and policy preferences. (244)

So if DeSantes and Smith are correct, then the hope that America’s conflicts over race and racism will disappear as a result of generational replacement is not likely to materialize. Instead, positive and purposeful steps will be needed in the realm of public and semi-public policy in order to address the effects of discrimination and prejudice. And since the burdens of discrimination are cumulative, it is not enough to ensure that opportunities are available on the basis of merit and achievement to solve the problem. If residential segregation makes it less likely that black children will receive equal educational opportunities, then all of their opportunities in later life will be stunted as well. If elementary schools or high schools are racially oriented so that black children on average receive lower quality educations, then “equal opportunity” at the university level is insufficient.

DeSante and Smith do not have much to say about what a “non-racist” mentality and culture would look like, but we can extend their thinking by emphasizing the importance of “education for an inclusive multicultural democracy”. This is a view of “civic education” for all of us based on respect across our various lines of division. A major part of such an education is a clear and honest knowledge of some of the sources of racist oppression and violence that have burdened our society in the past. Another is a deliberate and creative effort by educators, leaders, and students themselves to find our way to some of the ideals articulated by MLK and the beloved community. Without some idea of how young people can be genuinely transformed in their underlying attitudes about race, it is hard to see how the “stagnation of racial attitudes” called out by DeSante and Smith can be disrupted and reimagined. (Here is a more extensive discussion of what is needed for an inclusive multicultural democracy to become a reality; link.)