We often speak of government as if it has intentions, beliefs, fears, plans, and phobias. This sounds a lot like a mind. But this impression is fundamentally misleading. "Government" is not a conscious entity with a unified apperception of the world and its own intentions. So it is worth teasing out the ways in which government nonetheless arrives at "beliefs", "intentions", and "decisions".

Let's first address the question of the mythical unity of government. In brief, government is not one unified thing. Rather, it is an extended network of offices, bureaus, departments, analysts, decision-makers, and authority structures, each of which has its own reticulated internal structure.

This has an important consequence. Instead of asking "what is the policy of the United States government towards Africa?", we are driven to ask subordinate questions: what are the policies towards Africa of the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Commerce, the Central Intelligence Agency, or the Agency for International Development? And for each of these departments we are forced to recognize that each is itself a large bureaucracy, with sub-units that have chosen or adapted their own working policy objectives and priorities. There are chief executives at a range of levels -- President of the United States, Secretary of State, Secretary of Defense, Director of CIA -- and each often has the aspiration of directing his or her organization as a tightly unified and purposive unit. But it is perfectly plain that the behavior of functional units within agencies are only loosely controlled by the will of the executive. This does not mean that executives have no control over the activities and priorities of subordinate units. But it does reflect a simple and unavoidable fact about large organizations. An organization is more like a slime mold than it is like a control algorithm in a factory.

This said, organizational units at all levels arrive at something analogous to beliefs (assessments of fact and probable future outcomes), assessments of priorities and their interactions, plans, and decisions (actions to take in the near and intermediate future). And governments make decisions at the highest level (leave the EU, raise taxes on fuel, prohibit immigration from certain countries, ...). How does the analytical and factual part of this process proceed? And how does the decision-making part unfold?

One factor is particularly evident in the current political environment in the United States. Sometimes the analysis and decision-making activities of government are short-circuited and taken by individual executives without an underlying organizational process. A president arrives at his view of the facts of global climate change based on his "gut instincts" rather than an objective and disinterested assessment of the scientific analysis available to him. An Administrator of the EPA acts to eliminate long-standing environmental protections based on his own particular ideological and personal interests. A Secretary of the Department of Energy takes leadership of the department without requesting a briefing on any of its current projects. These are instances of the dictator strategy (in the social-choice sense), where a single actor substitutes his will for the collective aggregation of beliefs and desires associated with both bureaucracy and democracy. In this instance the answer to our question is a simple one: in cases like these government has beliefs and intentions because particular actors have beliefs and intentions and those actors have the power and authority to impose their beliefs and intentions on government.

The more interesting cases involve situations where there is a genuine collective process through which analysis and assessment takes place (of facts and priorities), and through which strategies are considered and ultimately adopted. Agencies usually make decisions through extended and formalized processes. There is generally an organized process of fact gathering and scientific assessment, followed by an assessment of various policy options with public exposure. Final a policy is adopted (the moment of decision).

The decision by the EPA to ban DDT in 1972 is illustrative (link, link, link). This was a decision of government which thereby became the will of government. It was the result of several important sub-processes: citizen and NGO activism about the possible toxic harms created by DDT, non-governmental scientific research assessing the toxicity of DDT, an internal EPA process designed to assess the scientific conclusions about the environmental and human-health effects of DDT, an analysis of the competing priorities involved in this issue (farming, forestry, and malaria control versus public health), and a decision recommended to the Administrator and adopted that concluded that the priority of public health and environmental safety was weightier than the economic interests served by the use of the pesticide.

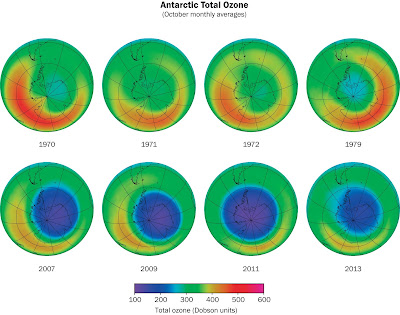

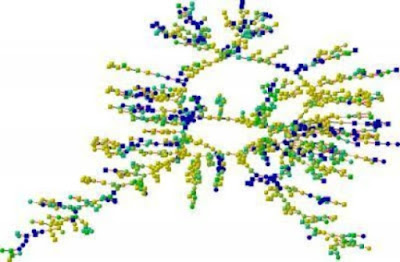

Other examples of agency decision-making follow a similar pattern. The development of policy concerning science and technology is particularly interesting in this context. Consider, for example, Susan Wright (link) on the politics of regulation of recombinant DNA. This issue is explored more fully in her book Molecular Politics: Developing American and British Regulatory Policy for Genetic Engineering, 1972-1982. This is a good case study of "government making up its mind". Another interesting case study is the development of US policy concerning ozone depletion; link.

These cases of science and technology policy illustrate two dimensions of the processes through which a government agency "makes up its mind" about a complex issue. There is an analytical component in which the scientific facts and the policy goals and priorities are gathered and assessed. And there is a decision-making component in which these analytical findings are crafted into a decision -- a policy, a set of regulations, or a funding program, for example. It is routine in science and technology policy studies to observe that there is commonly a substantial degree of intertwining between factual judgments and political preferences and influences brought to bear by powerful outsiders. (Here is an earlier discussion of these processes; link.)

Ideally we would like to imagine a process of government decision-making that proceeds along these lines: careful gathering and assessment of the best available scientific evidence about an issue through expert specialist panels and sections; careful analysis of the consequences of available policy choices measured against a clear understanding of goals and priorities of the government; and selection of a policy or action that is best, all things considered, for forwarding the public interest and minimizing public harms. Unfortunately, as the experience of government policies concerning climate change in both the Bush administration and the Trump administration illustrates, ideology and private interest distort every phase of this idealized process.

(Philip Tetlock's Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction offers an interesting analysis of the process of expert factual assessment and prediction. Particularly interesting is his treatment of intelligence estimates.)