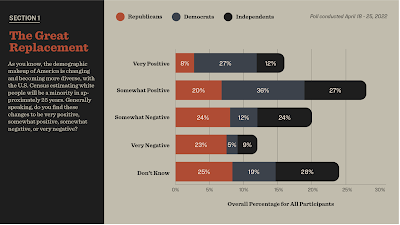

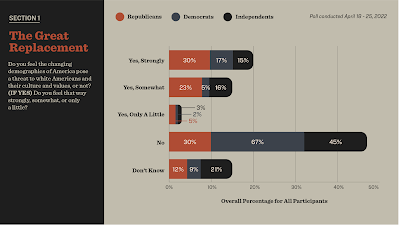

The increase in public belief in core claims of far-right extremism in the United States is alarming. Central among those beliefs is the "Great Replacement" theory advocated by Fox News pundits, and contributing to white supremacist mobilization and violence. The Southern Poverty Law Center conducted a public opinion survey in spring 2022 (link) and found "substantial public support" for "great replacement" theory; and, not surprisingly, this support differed significantly by party affiliation, gender, and age. Here are several particularly striking tables from the report.

Far-right ideologies are hierarchical and exclusionary. They establish clear lines of superiority and inferiority according to race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, religion, and sexuality. This includes a range of racist, anti-immigrant, nativist, nationalist, white-supremacist, anti-Islam, anti-Semitic, and anti-LGBTQ+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and others) beliefs. At their extreme, these are ideologies that dehumanize groups of people who are deemed to be inferior, in ways that have justified generations of violence in such forms as white supremacy, patriarchy, Christian supremacy, and compulsory heterosexuality. These kinds of ideologies have imbued individuals from the dominant groups with a sense of perceived superiority over others: slaves, nonwhites, women, non-Christians, or the LGBTQ+ community. (6)

Miller-Idriss focuses on "youth" mobilization -- not because this is the only segment of population that is active in far-right activism and violence, but because success with young people lays the ground for an even greater level of activism in the future.

In this light, the efforts of organized far-right groups to engage with young people in the spaces and places described in this book—combat sports and MMA clubs, music scenes, YouTube cooking channels, college campuses, and a variety of youth-oriented online spaces like gaming chatrooms or social-media platforms—are especially important. Far-right groups have always worked to recruit young people to their movements and politicize youth spaces like concerts, festivals, youth-oriented events, and music lyrics. These are sometimes referred to as youth “scenes”—a word that reflects a less hierarchical and more disorganized structure than traditional social movements. Today there exists a broader range of spaces, places, and scenes to engage young people in the far right. Older leaders in far-right movements rely on college students for speaking invitations and campus activism. They recruit young people to join boxing gyms and compete in combat sports tournaments. Propaganda videos featuring fit, young men in training camps and shooting ranges use music and imagery clearly oriented toward younger recruits. (23-24)

And she emphasizes that the majority of these young people are men.

It’s not only youth who drive most of the violence on the far right, of course. Mostly, it’s youth who are men. There is much to say about masculinity and toxic masculinity as drivers of far-right violence in both online and off-line contexts, through online harassment and trolling as well as physical violence against others. It’s also important to note that we have seen and are still seeing increasing participation of women in the far right, including in violent fringe and terrorist groups. Women also enable the far right in important ways, whether through YouTube cooking videos that create a softer entry or by playing more supportive roles in extremist movements as mothers, partners, and wives who help to reproduce white nations. (24-25)

Miller-Idriss describes a progression of engagement with far-right activism:

Far-right youth today might initially encounter extremist narratives through chance encounters in mainstream spaces like the MMA, a campus auditorium, a podcast, or a YouTube video. Each of those mainstream spaces, however, can act as a channel, opening the door to dedicated far-right MMA festivals, alt-tech platforms and encrypted communication platforms, and dedicated YouTube subscriptions that mix mainstream interest in cooking or music with far-right ideology. Understanding these new spaces and places—the geography of hate—is key to comprehending the far right in its modern form. (25-26)

This approach emphasizes the importance of studying the spaces within which far-right extremist narratives are conveyed and where they find the beginnings of a mass audience. And she points out that memes of "place and space" play a major role in the narratives of the far right -- in polemics and in popular culture:

Fans of one clothing brand that is well-known for its use of far-right symbols could connect with other brand fans and learn about in-person meet-ups on a now-defunct Tumblr blog. In 2016, this included an announcement of a one-week trip to the “lands of Hyperborea—a mythical pre-historic motherland of our race”—in the region of the Karelia and Kola Peninsula in northwest Russia. Hyperborea was also the name of a prior clothing product line for the German brand Ansgar Aryan, which featured website and catalog text that explained the importance of Hyperborea and described its epic battle between the people of the “light” and the “dark men.” (37)

An especially interesting feature of M-I's research focuses on clothing style within popular culture, and the symbolic importance that far-right extremists place on "costume":

For a generation of adults who grew up with images of far-right extremists as racist Nazi skinheads, far-right aesthetics had clear signals: a uniform style of shaved heads, high black combat boots, and leather bomber jackets. You would be hard-pressed to find a bomber jacket in far-right youth scenes today. The past few years have seen a dramatic shift in the aesthetics of far-right extremism, as the far right has all but abandoned the shaved heads and combat boots of the racist skinhead in favor of a hip, youth-oriented style that blends in with the mainstream. (62)

In the years since white-supremacist blogger Andrew Anglin urged his followers to dress in “hip” and “cool” ways at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, far-right fashion has rapidly evolved. The clean-cut aesthetic of the white polo shirts and khakis that drew national attention in 2017 has been supplanted by new brands marketing the far right, with messages and symbols embedded in clothing to convey white-supremacist ideology. (78)

In Northwest Washington, DC, I glanced out of my office window and saw a young man with an imperial eagle emblazoned across his jacket—part of a British fashion brand’s controversial logo, which has been likened to the Nazi eagle symbol. Later that year, I shared a campus elevator with a man wearing a “patriotic” brand T-shirt whose advertising tagline is “forcing hipsters into their safe space, one shirt at a time.” Symbols and messaging on otherwise ordinary clothing help signal connections to far-right ideology and organized movements—like the torch-bearing Charlottesville marcher, for example, whose polo shirt bore a logo from the white-supremacist group Identity Evropa. (78-79)

And what is the function of extremist branding of clothing? It is to establish "signaling" among a group of people, and to "mainstream" the messages of the hate-based extremist right.

Hate clothing celebrates violence in the name of a cause—often using patriotic images and phrases and calls to act like an American, along with Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, and white-supremacist messages. In this way, far-right clothing links patriotism with violence and xenophobia. On one T-shirt, a saluting, grimacing emoji wielding a semiautomatic gun replaces the stars in the American flag, overlaid with the words “locked-n-loaded;” on the back of the T-shirt, the text reads “White American/Hated by Many/Zero F#cks Given.” In the “about” section of the website, the company explains it was “not founded on prejudice, seperatism (sic) or racism, but simply out of pride.” (80)

M-I also notes the importance of extremist music in the mobilization of young people:

New genres of racist music—such as “fashwave” (fascism wave, a variant of electronic music) and white-power country and pop—have broadened far-right music scenes far beyond the hard rock style typically associated with white-power music. Across the globe, the commercial and cultural spaces the far right uses to reach new audiences and communicate its ideologies have expanded rapidly—aided in no small part by social media and “brand fan” image-sharing sites that help promote and circulate new products. (69-70)

And these fashions in extremist music have effect in the broader population:

Decades of research on far-right youth culture has shown how particular facets of subcultures and youth scenes—like hate music—can spread intolerance and prejudice against minorities, not only in expected genres like right-wing hard rock and black metal, but also in more mainstream genres like country and pop music. (82)

The most surprising part of M-I's book is her treatment of fight clubs and mixed martial arts. She regards these as important vectors of extremist mobilization in many countries.

By the mid-2000s, MMA gyms across the European continent had developed a reputation as places where far-right youth were recruited and radicalized. This was a significant shift for violent far-right youth scenes, which had previously been oriented around soccer hooliganism and stadium brawls, but were now gravitating toward the MMA world. Journalists, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), think tanks, and watchdog groups have documented connections between the MMA world and white supremacists across Europe and North America. (97)

In retrospect, it isn’t surprising that the far right homed in on MMA and other combat sports like jujitsu and boxing as a perfect way to channel ideologies and narratives about national defense, military-style discipline, masculinity, and physical fitness to mainstream markets. Hitler himself had advocated for the importance of combat sports for training Nazi soldiers. The National Socialist Sturmabteilung (storm division, or storm troopers) incorporated not only calisthenics but also boxing and jujitsu as a core part of training for street fights. (95)

She notes that this phenomenon is under-studied in North America, but equally present.

MMA is a perfect incubator for the far right. It helps recruit new youth to the movement from adjacent subcultures, introducing key far-right messages about discipline, resistance to the mainstream, and apocalyptic battles. The combat-sports scene helps the far right motivate youth around ideals related to physical fitness, strength, combat, and violence. This mobilization calls on youth to train physically to defend the nation and white European civilization against the dual threats posed by immigrants and the degenerate left. At the same time, MMA and combat sports reinforce dominant ideals about masculinity and being a man—related not only to violence, risk, and danger but also to solidarity, brotherhood, and bonding.47 The MMA world also helps radicalize and mobilize youth by intensifying far-right ideals about masculinity and violence and the range of exclusionary and dehumanizing ideologies that relate to the supposed incursion of immigrants, the coming of “Eurabia,” “white genocide,” or the “great replacement.” (100-101)

MMA also has the advantage of a built-in structure to reach out to groups of young men through local gyms’ efforts to increase profitability and broaden their client base. Local MMA gyms in the United States, for example, regularly host live sparring demonstrations for broader communities—at open houses, martial-arts facilities, fraternity houses, and university and community centers—to promote their gyms. (104)

In addition to these aspects of cultural mobilization on the far right, M-I also sheds light on the increase that has occurred on university campuses in the open promulgation of extremist speech and mobilization and the sustained attack on the supposed "cultural Marxism" endemic in university faculties.

Propaganda, white-supremacist fliers, racist graffiti, and provocative speaking tours have brought hate to campuses across the country in new ways, exposing hundreds of thousands of students to far-right ideologies. This kind of hate intimidates and threatens members of vulnerable groups, unsettles campus climates, and creates significant anxiety around student safety and well-being. Students at Syracuse University who staged a sit-in in November 2019 following more than a dozen hate incidents at the university told journalists that they didn’t feel safe on campus. (120)

There is much more of interest in Hate in the Homeland. The book should be priority reading for anyone interested in stemming the rise of extremism in western liberal democracies.

2 comments:

I have had discussions with associates, mostly moderates, about this topic. My older brother summed things up pretty well: without cooperation, there is no civilization. Extremists do not count themselves anti-civilization. They wear blinders, crafted by anarchy and insurrection, asserting something like: this is not the way things are supposed to be, WE know how things should be. I have friends, living calmer expatriate lives in several parts of the world. They miss some aspects of life as Americans, but would not return for love or money. Sadly, it seems to me there is no solution to this. We there to be one, it would be draconian, affecting all in order to impede a few. That would not be America either. So we have come to entropy via complexity, a figurative black hole, subsuming much of the progress which brought us here.

Slightly off topic, but a question about the replacement theory stuff. A lot of coverage of it in the media and among academics (e.g. here) treats it like a wingnut conspiracy theory, an extremist belief, etc. But it's not hard to see how the way that many progressives talk about racial justice nurtures and encourages the belief. It has become increasingly common, for example, to use the term "white supremacy" to describe any institution in which whites form the numerical majority (i.e. minorities are underrepresented). This is reinforced by a lot of "white privilege" checklists, which systematically confuse racial privilege with majority privilege. In both cases, the expansive use of these terms implies that the only way to combat white supremacy, or white privilege, is to make it so that whites are no longer a demographic majority.

So that part is not a conspiracy theory, it's a pretty literal reading of what people at the progressive end of the Democratic party (woke/DEI/etc.) have been saying for a while. Plus ever since The Emerging Democratic Majority there has been a lot of excitement among Democrats about the declining number of white voters, so that's not a conspiracy either. The conspiracy part is when conservatives connect up this idea that racial justice requires demographic transformation with liberal support for abortion and increased immigration (the former to reduce the number of whites, the latter to increase the number of non-whites). THAT part is obviously a conspiracy theory, in the sense that it is an exercise in connect-the-dots thinking where there isn't actually any connection. Still, it seems to me that about 80% of replacement theory comes from just listening to what left-liberals are saying, and maybe 20% from further paranoia. Am I mistaken about this?

Post a Comment