In Dissecting the Social Peter Hedström describes the analytical sociology approach in these terms:

Although the term analytical sociology is not commonly used, the type of sociology designated by the term has an important history that can be traced back to the works of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century sociologists such as Max Weber and Alexis de Tocqueville, and to prominent mid-twentieth-century sociologists such as the early Talcott Parsons and Robert K. Merton. Among contemporary social scientists, four in particular have profoundly influenced the analytical approach. They are Jon Elster, Raymond Boudon, Thomas Schelling and James Coleman. (Dissecting the Social, kl 113)

And here is how Hedström and Bearman describe the approach in their introduction to The Oxford Handbook of Analytical Sociology:

Analytical sociology is concerned first and foremost with explaining important social facts such as network structures, patterns of residential segregation, typical beliefs, cultural tastes, common ways of acting, and so forth. It explains such facts not merely by relating them to other social facts -- an exercise that does not provide an explanation -- but by detailing in clear and precise ways the mechanisms through which the social facts under consideration are brought about. In short, analytical sociology is a strategy for understanding the social world. (Hedström and Bearman, eds. 2009 : 3-4)

Peter Demeulenaere makes several important points to further specify AS in his extensive introduction to Analytical Sociology and Social Mechanisms. He holds that AS is not just another new paradigm for sociology. Instead, it is a reconstruction of what valid explanations on sociology must look like, once we properly understand the logic of the social world. He believes that much existing sociology conforms to this set of standards -- but not all. And the non-conformers are evidently judged non-explanatory. For example, he writes, “Analytical sociology should not therefore be seen as a manifesto for one particular way of doing sociology as compared with others, but as an effort to clarify (“analytically”) theoretical and epistemological principles which underlie any satisfactory way of doing sociology (and, in fact, any social science)” (Demeulenaere, ed. kl 121). So this sets a claim of a very high level of authority over the whole field, implying that other decisions about explanation, ontology, and method are less than fully scientific.

Analytical sociology rests on three central ideas.

First, there is the idea that social outcomes need to be explained on the basis of the actions of individuals. Hedstrom, Demeulenaere, and their colleagues refer to this position as methodological individualism. It is often illustrated by reference to "Coleman's Boat" in James Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory (Coleman, 1990, 8) describing the relationship that ought to exist between macro and micro social phenomena (link). The boat diagram indicates the relationship between macro-factors (Protestant religious doctrine, capitalism) and the micro factors that underlie their causal relation (values, economic behavior). Here are a few of Hedström's formulations of this ontological position:

In sociological inquiries, however, the core entity always tends to be the actors in the social system being analyzed, and the core activity tends to be the actions of these actors. (Dissecting, kl 106)

To be explanatory a theory must specify the set of causal mechanisms that are likely to have brought about the change, and this requires one to demonstrate how macro states at one point in time influence individuals' actions, and how these actions bring about new macro states at a later point in time. (Dissecting, kl 143)

In other words: according to analytical sociologists, a good explanation of a given social outcome is a demonstration of how this outcome is the aggregate result of structured individual actions. In particular, an explanation should not make reference to meso or macro level factors.

In his introduction to Analytical Sociology and Social Mechanisms Demeulenaere provides an analysis of the doctrine of methodological individualism and its current status. He believes that criticisms of MI have usually rested on a small number of misunderstandings which he attempts to resolve. For example, MI is not "atomistic", "egoistic", "non-social", or exclusively tied to rational choice theory. He prefers a refinement that he describes as structural individualism, but essentially he argues that MI is a universal requirement on social science. Demeulenaere specifically disputes the idea that MI implies a separation between society and non-social individuals. That said, Demeulenaere fully endorses the idea that AS depends upon and presupposes MI: “Does analytical sociology differ significantly from the initial project of MI? I do not really think so. But by introducing the notion of analytical sociology we are able to make a fresh start and avoid the various misunderstandings now commonly attached to MI” (Demeulenaere ed. kl 318).

A theory based on the individual needs to have a theory of the actor. Hedström and others in the AS field are drawn to a broad version of rational-choice theory -- what Hedström calls the "Desire-Belief-Opportunity theory". This is a variant of rational choice theory, because the actor's choice is interpreted along these lines: given the desires the actor possesses, given the beliefs he/she has about the environment of choice, and given the opportunities he/she confronts, action A is a sensible way of satisfying the desires. (It is worth pointing out that it is possible to be microfoundationalist about macro outcomes while not assuming that individual actions are driven by rational calculations. Microfoundationalism is distinct from the assumption of individual rationality.)

Second is the idea that social actors are socially situated; the values, perceptions, emotions, and modes of reasoning of the actor are influenced by social institutions, and their current behavior is constrained and incentivized by existing institutions. (This position has a lot in common with the methodological localism; link.) Practitioners of analytical sociology are not atomistic about social behavior, at least in the way that economists tend to be; they want to leave room conceptually for the observation that social structures and norms influence individual behavior and that individuals are not unadorned utility maximizers. In the Hedström-Bearman introduction to the Handbook they refer to their position as “structural individualism”:

Structural individualism is a methodological doctrine according to which social facts should be explained as the intended or unintended outcomes of individuals’ actions. Structural individualism differs from traditional methodological individualism in attributing substantial explanatory importance to the social structures in which individuals are embedded. (Hedström and Bearman, 2009, 4).

Demeulenaere explicates the term by referring to Homans’ distinction between individualistic sociology and structural sociology; the latter “is concerned with the effects these structures, once created and maintained, have on the behaviour of individuals or categories of individuals” (Demeulenaere, Analytical Sociology and Social Mechanisms, 2011, introduction, quoting Homans, 1984). So “structural individualism” seems to amount to this: the behavior and motivations of individuals are influenced by the social arrangements in which they find themselves.

This is a direction of thought that is not well developed within analytical sociology, but would repay further research. There is no reason why a methodological-individualist approach should not take seriously the causal dynamics of identity formation and the formation of the individual's cognitive, practical, and emotional frameworks. These are relevant to behavior, and they are plainly driven by concrete social processes and institutions.

Third, and most distinctive, is the idea that social explanations need to be grounded in hypotheses about the concrete social causal mechanisms that constitute the causal connection between one event and another. Mechanisms rather than regularities or necessary/sufficient conditions provide the fundamental grounding of causal relations and need to be at the center of causal research. This approach has several intellectual foundations, but one is the tradition of critical realism and some of the ideas developed by Roy Bhaskar (link).

Here is Hedström's statement of the position:

The position taken here, rather, is that mechanism-based explanations are the most appropriate type of explanations for the social sciences. The core idea behind the mechanism approach is that we explain a social phenomenon by referring to a constellation of entities and activities, typically actors and their actions, that are linked to one another in such a way that they regularly bring about the type of phenomenon we seek to explain. (Dissecting, kl 65)

A social mechanism, as defined here, is a constellation of entities and activities that are linked to one another in such a way that they regularly bring about a particular type of outcome. (kl 181)

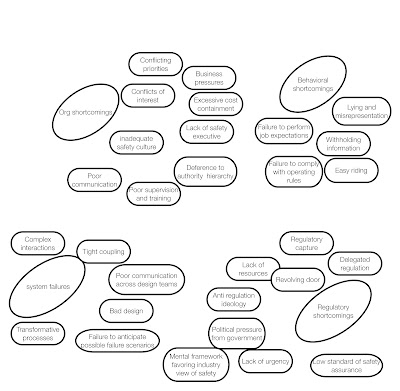

Demeulenaere also emphasizes that AS depends closely on the methodology of social causal mechanisms. The "analytical" part of the phrase involves identifying separate things, and the social mechanisms idea says how these things are related. Causal mechanisms are expected to be the components of the linkages between events or processes hypothesized to bear a causal relation to each other. And, more specifically to the AS approach, the mechanisms are supposed to occur at the level of the actors--not at the meso or macro levels. So this means that AS would not countenance a meso-level mechanism like this: "the organizational form of the supervision structure at the Bhopal chemical plant caused a high rate of maintenance lapses that caused the accidental release of chemicals." The organizational form is a meso-level factor, and it would appear that AS would require that its causal properties be unpacked onto individual actors' behavior. (I, on the other hand, will argue below that this is a perfectly legitimate social mechanism because we can readily supply its microfoundations at the behavioral level. So this suggests that we can legitimately refer to meso-level mechanisms as long as we are mindful of the microfoundations requirement. And this corresponds as well to the tangible fact that institutions have causal force with respect to individuals. Here is an earlier discussion; link.)

In addition to these three orienting frameworks for analytical sociology, there is a fourth characteristic that should be mentioned. This is the idea that the tools of computer-based simulation of the aggregate consequences of individual behavior can be a very powerful tool for sociological research and explanation. So the tools of agent-based modeling and other simulations of complex systems have a very natural place within the armoire of analytical sociology. These techniques offer tractable methods for aggregating the effects of lower-level features of social life onto higher-level outcomes. If we represent actors as possessing characteristics of action X, Y, Z, and we represent their relations as U, V, W -- how do these actors in social settings aggregate to mid- and higher-level social patterns? This is the key methodological challenge that sociologists like Gianluca Manzo have explored (Agent-based Models and Causal Inference), and it produces very interesting results.

This brief summary of the central doctrines of AS provides one reason why AS theorists are so concerned to have adequate and tractable models of the actor -- often rational actor models. Thomas Schelling's work provides a particularly key example for the AS research community; in field after field he demonstrates how micro motives aggregate onto macro outcomes (Schelling, 1978, 1984). And Elster's work is also key, in that he provides some theoretical machinery for analyzing the actor at a "thicker" level -- imperfect rationality, self-deception, emotion, commitment, and impulse (Elster, Ulysses and the Sirens).

In short, analytical sociology is a compact, clear approach to the problem of understanding social outcomes. It lays the ground for the productive body of research questions associated with the "aggregation dynamics" research program. There is active, innovative research being done within this framework of ideas, especially in Germany, Sweden, and Great Britain. And its clarity permits, in turn, the formulation of rather specific critiques from researchers in other sociological traditions who reject one or another of the key components. However, the framework of analytical sociology should not be mistaken for a general approach to all sociological research and explanation. It is well suited to some problems, and less so to others.

(Here is an earlier post summarizing Peter Demeulenaere's account of analytical sociology; link.)