For the past six months or so I've been wrestling with how to reformulate my own thinking about the nature of the social world -- the nature of "social reality" (link). I've come to realize that the position I've defended for years -- ontological individualism -- is still too dependent on the view of "social entities sitting on top of individual actors", which is no longer convincing to me. And I've reformulated what I have to say about "actor-centered sociology" and "microfoundations" accordingly. I am now more satisfied with the position I've come to -- a diachronic view of intertwined and mutually influencing processes at the social level and the individual-actor level, and an associated view that suggests that both social arrangements and features of individual agency are fluid and "fluxy". Here are two key statements from "Rethinking Ontological Individualism" in its final draft:

Actors and structures are linked in inseparable loops of mutual influence over time, with both actors and structures dependent on the current ensemble of “actors-within-structures” within which they have developed, changed, and persisted. The social world is thus inherently indeterminate, reflecting unpredictable changes in all its elements over time.

...

This view has important ontological implications. For one thing, it implies that neither actors nor structures have “essential natures” or fixed and unchanging properties. Rather, the properties of social structures are influenced by the past and present actions and thoughts of actors and the prior characteristics of structures; while the mental characteristics of present actors are shaped by the ambient social arrangements within which they develop. (There is a biological precondition: human beings must be the kinds of “cognitive-practical machines” that can embody very extensive change; Gibbard 1990.) Further, actors are influenced by ambient structures (external causes); but a given generation of actors is capable of genuine innovation and creativity (internal causes). Susan B. Anthony was influenced by her suffragist predecessors and contemporaries, but she also brought her own innovative thinking to the struggle for full rights of citizenship for women in 1872. And likewise, structures are modified by generations of actors (external causes), but structures also create opportunities for structural innovation (internal causes).

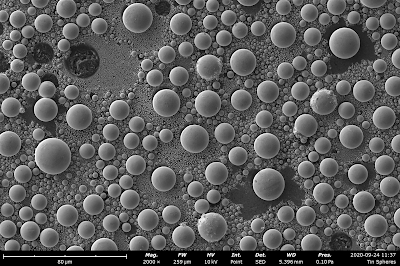

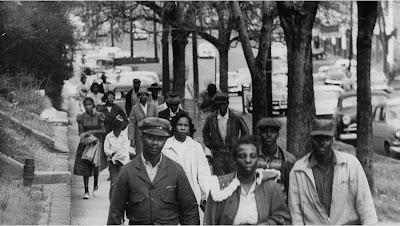

What is striking to me now that this process of exploration and reformulation has come to something like a conclusion is how much the resulting position sounds like a version of "process metaphysics" -- the idea that processes of change rather than fixed underlying particles should be the fundamental ontological category. (The images above are selected to illustrate the two metaphysical perspectives: the orderly composition of a metal from its constituent atoms (substance metaphysics) and the contingent and entangled creation of a social movement (process metaphysics).) Process metaphysics is distinctly a minority position in analytical philosophy today, so it is striking to me that some of the basic intuitions of that view developed organically out of a consideration of how social structures, institutions, and actors interact to constitute the social world -- "social reality". I didn't begin with the premises of process metaphysics, but rather developed a conception that bore important similarities to process metaphysics.

What is process philosophy? Consider the opening sentences of Johanna Seibt’s treatment of process philosophy in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Process philosophy is based on the premise that being is dynamic and that the dynamic nature of being should be the primary focus of any comprehensive philosophical account of reality and our place within it. Even though we experience our world and ourselves as continuously changing, Western metaphysics has long been obsessed with describing reality as an assembly of static individuals whose dynamic features are either taken to be mere appearances or ontologically secondary and derivative. For process philosophers the adventure of philosophy begins with a set of problems that traditional metaphysics marginalizes or even sidesteps altogether: what is dynamicity or becoming—if it is the way we experience reality, how should we interpret this metaphysically? (link)

13 comments:

In Mead's final years, he was really interested in processual metaphysics.

Moran, Jon S. 1996. “Bergsonian Sources of Mead’s Philosophy.” Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society 32(1):41–63.

However, in Abbott's writing, Time Matters, he made a distinction between the two scholars and turned from Mead to Whitehead..

The language of modern inquiry always fascinates me. Aligning *process metaphysics*with physics by introducing a particle metaphor into the discussion is an example. I understand there is a new book out by John Perry of Stanford---I think he is still there? He talks about Frege, context, reference and other matters and I hope to read the work. It is also interesting that I began thinking about what I have called *contextual reality* for awhile and have written a draft paper thereon. Connections interest me. The late Ken Taylor, also of Stanford, was working on a reference project. Osmosis and collegiality are wonderful things. Your mention of Susan B. Anthony is somewhat illustrative. My family physician, a D.O., used to say in relation to human anatomy and physiology: " it is all connected". I think connections are important in many areas of inquiry and study.

Maybe, besides the processes, the fluidity and the 'fluxy', we can also consider solidification and cristallisation to certain degrees and for certain periods. More concretely the presence of, for instance: character, effect of trauma, radicalisation, ... and as more physical examples: written constitutions, roads, ...

Dirk, yes, certainly you are correct. Both change and stability are features of the social world. Dupre makes the same point about the biological realm as well. And Kathleen Thelen takes this as a central part of her research problem in How Institutions Evolve: both stability and change require explanation. Thanks for your comment. Dan

Searle talked about constitutive and institutional rules. And, direction of fit world to mind and mind to world. WE make all of that up, as we go,as contextual reality, which emerges from interests, preferences and motives. It is not profound. has been there, since long before Donaldson's propositional attitudes. I truly hope new efforts here will produce something. Even though they may subsume my own. B.B. King, on his death bed, extolled Buddy Guy not to let the blues die. Exactly. It is all connected.

I'm delighted that you have found this convergence. Whitehead's process metaphysics has always appealed to me but I didn't make the connection.

Whitehead thought his metaphysics worked for the natural as well as the social sciences. I think you can easily find physicists and chemists who are willing to take a process view of their subjects, since each entity at every level (molecules, atoms, "elementary" particles, ...) is open to transformation -- and often such transformation is the focus of investigation. As in the social world, the eternal stability of any part of the material world can't be taken for granted.

Luckily for us, most of the time, most aspects of the social and material world are stable enough that we don't have to constantly monitor and reassess them. Our typical preference for a mostly static ontology rests mainly on a desire for cognitive economy, not any deep analysis.

We do need to invest a lot more thought in how (relatively) stable social structure arises and sustains itself in flux. To a first approximation the answer is fixed points (recurrence) in the flux, but we need to develop a much richer language to describe the range of causal mechanisms in the immense diversity of institutions.

Thanks, Jed, for these very helpful comments ... It was something of a surprise to me to find this parallel. Dan

Worth a look at Professor Collins's slant on sociology- the fundamental unit rather than being the individual or the group is the interaction- Durkheim and Goffman and Weber influenced him the most.

Not sure how his work will affect yours- he is at the sociological eye- maybe you're aware of his work-

"But perhaps physics and chemistry are bad models for thinking about metaphysics in general". On the contrary, modern physics leaves us with huge dilemmas - wave-particle duality, string theory, big bang and so on. Process and ontology are heavily implicated in the historical development of those areas and of those subjects as a whole.

Please disregard my previous comment, which referred in part to that from Denis, on August 8. I had to re-read most of this in order to make sense of it. I think the quote from your article regarding *bad models* is spot on. Physics and chemistry are different to metaphysics. The comment mentioned confused me because the second part of it seemed at odds with the quote. In other words, the commenter appeared to agree with what you wrote, but digressed into a diatribe on the short-comings of modern physics.

Again, I was confused---but agree with your observation.

Dear Dan - I used to read your blog more regularly (back when blogging, and blog reading, was something many more of us did regularly). I'm just catching up on this post now. It thrills me to see you move to a process-philosophical position. I've been developing such a position, partly in books and articles and partly on this blog - https://blog.uvm.edu/immanence/ - for a while now, but have never applied it with any real rigor to the social. I'm very eager to see how you develop your social ontology in a more processual direction.

All the best,

Adrian

Thanks, Adrian, I visited "Process-relational theory primer" on your blog and found it helpful. Thanks for the link.

Dan

Post a Comment